For the second time in four years, a proposal for a voluntary agreement between agencies and water contractors on flows into and through the Delta from the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers and their tributaries is wending its way through the State Water Resources Control Board. The proposal, which would replace the regime outlined in the Board’s most recent update to the Bay-Delta Plan, calls for substantially less water remaining in the system than the update, but comparing the two requires understanding some terminology, specifically the concept of “unimpaired flows.”

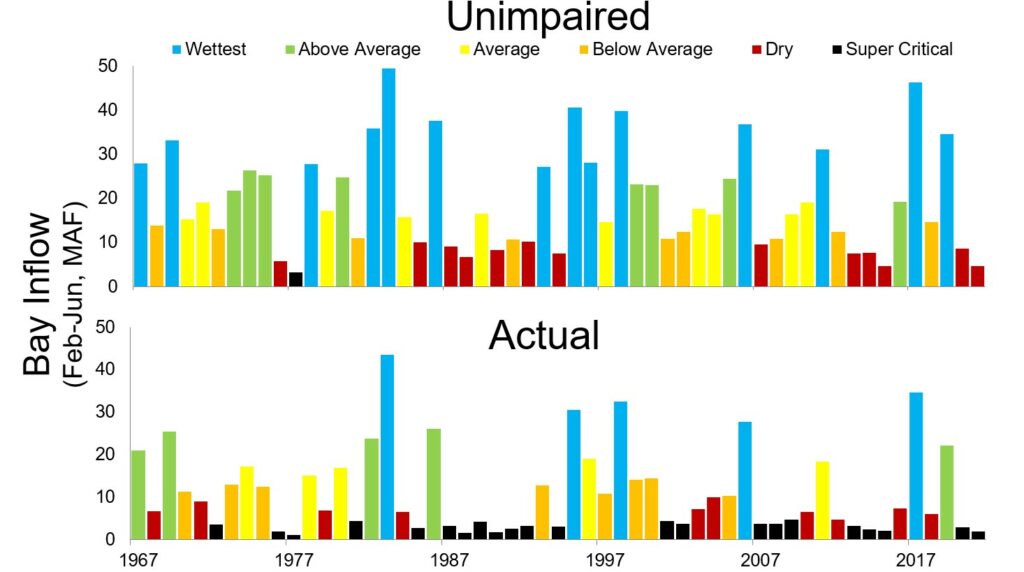

In 2018 the State Board adopted Phase 1 of the Bay-Delta Plan update, calling for San Joaquin River inflows to the Delta of 40% of unimpaired flow; a framework for the Sacramento River and its tributaries (yet to be formally adopted) would require 45%-65% of unimpaired flow into the Delta. The framework describes unimpaired flow as “the flow that would accumulate in surface waters in response to rainfall and snowmelt and flow downstream if there were no reservoirs or diversions to change the quantity, timing, and magnitude of flows.”

“In general, the unimpaired flow of a stream at a given location represents the magnitude of the flow that would occur at that location if there were no upstream impairments caused by agricultural or urban developments,” says the Department of Water Resources Tariq Kadir. Such impairments might include surface water diversions, or reservoir storage operations (if a reservoir exists). For a most upstream watershed, the unimpaired flow can be calculated by starting with the “impaired” (measured or estimated) stream flow at a gaged location and then modify the value by adding in, or subtracting out, all upstream impacts. For example, an upstream surface water diversion would be added in, since that water would show up at the gaged location if the diversion did not exist, or in the case of a surface reservoir, the water into the reservoir storage would be added to the gaged flow (since if the reservoir did not exist the water would show up at the gaged location), and water released from storage would be subtracted.

Unimpaired flow should be distinguished from natural flows in streams, which are the stream flows that would exist if all agricultural and urban land use developments were reverted to their native vegetative classes, all impacts of storage and diversions removed as well, and streams are channelized by natural levees (much lower than existing conditions, and thus subject to overtopping during high flow events).

The State Board’s Diane Riddle says unimpaired flow represents “the water that flows into the river in the existing configuration of the watershed” but without dams and other diversions, emphasizing that “it’s the existing landscape and the existing hydrology, not what would happen in a natural, unperturbed system.”

Unimpaired flow is useful as a measure of the total amount of water entering the watershed, says Riddle. “It gives us a sense of just how much water is available for different purposes, including human uses and environmental purposes.” She adds that it may be especially useful as the climate changes because “it automatically adjusts to variable hydrology.”

Generally, unimpaired flow is calculated as seven-day running average, says Riddle. However, the Bay-Delta Plan framework includes implementation provisions that could allow for a different timeframe—possibly weeks or months—so that flows could be “shaped” to “maximize the benefits from the quantity of water available for environmental purposes,” she says.

In this case, some amount of water representing a specific percentage of unimpaired flow over a certain time period is managed for specific objectives, rather than being released according to the natural hydrograph. San Francisco Baykeeper’s Jon Rosenfield, says this “block of water” approach may reduce the benefits of using unimpaired flow as a metric. “It loses a lot of the natural variation in timing that’s very beneficial,” he says.