It’s never easy (or cheap) to protect one species by manipulating the patterns of another. Nor is it always advisable. But there are times when it’s worth a shot, especially when multiple agencies and states are willing to get involved. To jump into this bird story that turns out to be a fish tale, we’ll start in the middle, when several years ago the US Army Corps of Engineers asked Don Edwards San Francisco National Wildlife Refuge to collaborate on a plan to improve nesting habitat at the Refuge for Caspian terns, the largest and stockiest of the terns.

“It was a win-win for us,” said Don Edwards wildlife biologist Cheryl Strong, who explained that the islands built for water bird nesting habitat in two of the ponds during the South Bay Salt Pond Habitat Restoration Project (ponds SF2 and A16) had enticed very few birds.

The Corps chose seven islands in these two ponds, five for the terns and two for snowy plovers to reduce potential nesting conflicts. The agency delivered tons of gravel and rock by barge and crane to enhance nesting conditions on the islands. To increase the chances that the birds would land, the Corps hired the US Geological Survey to entice the terns with social attraction. Caspian terns are noisy, social birds, and biologists trying to attract them to one nesting spot over another, provide recordings of bird calls and fake companions to simulate a happening scene. Terns are colonial birds. As they migrate north on the Pacific Flyway after spending the winter in southern climes as far as Northern Bolivia, these muscular, fish-eating, diving birds are more likely to stop when they see a colony of other terns.

So far, the numbers are promising. In 2015, USGS biologists counted 224 pairs of breeding birds with 174 fledgling chicks. In 2016, it was 317 breeding pairs with 158 fledglings.

It’s a pull-push approach, said Corps fish biologist David Trachtenbarg. “We’re essentially pushing terns out of the Columbian Basin and trying to pull them to nesting habitat in other locations on the West Coast,” he said.

Tern chick chirping. Video by Crystal Shore, USGS

Get a Move On

It’s not the first time that Caspian terns have been moved. In the early 1980s, they began showing up in greater numbers to the basin, including at Rice Island (river mile 21). With the ideal conditions of a sand substrate from dredging, good visibility, and no predators, the colony grew from 1,000 to 8,700 breeding pairs in a little over 10 years.

Simultaneously, more fish were being produced and tagged in an upstream hatchery. “That’s when we found out that juvenile salmonids, and specifically steelhead, were being impacted by this bird population,” says Corps biologist Paul Schmidt.

Biologists observed that approximately 90% of the terns’ diet at Rice Island was salmonids. In 1999, NOAA required that the Corps do something about the birds. Reasoning that they would do less damage if they had a wider palate of fish to choose from, the Corps moved the terns to East Sand Island by dissuading them from breeding on Rice Island with fencing and human hazing techniques, and by improving habitat at East Sand Island.

The birds complied, and they did expand their palates to include fish from the ocean. Nevertheless, the bird population continued to grow and they ate just as many fish. The agencies had another problem. The population of double-crested cormorants on East Sand Island also grew from 100 breeding pairs in 1989 to 15,000 pairs in 2013, leading to some controversial culls.

East Sand Island now has the largest breeding colonies of Caspian terns and double-crested cormorants in the world. NOAA required action to protect the fish again, and the push and pull plan of terns was implemented in 2006. The plan to redistribute the birds included improvement eight acres of tern nesting habitat in Eastern Oregon, Northern California, and the San Francisco Bay, and to reduce habitat at East Sand Island to one acre.

The pull is starting to work. The sites in Oregon and California have anywhere between 40 and 700 nesting pairs. The push, not so much. In their one-acre at East Sand Island, terns are nesting at higher densities than ever seen before. “They really want to stay at East Sand Island and not leave the Columbia River estuary,” said Schmidt.

Taking a Turn in San Francisco Bay

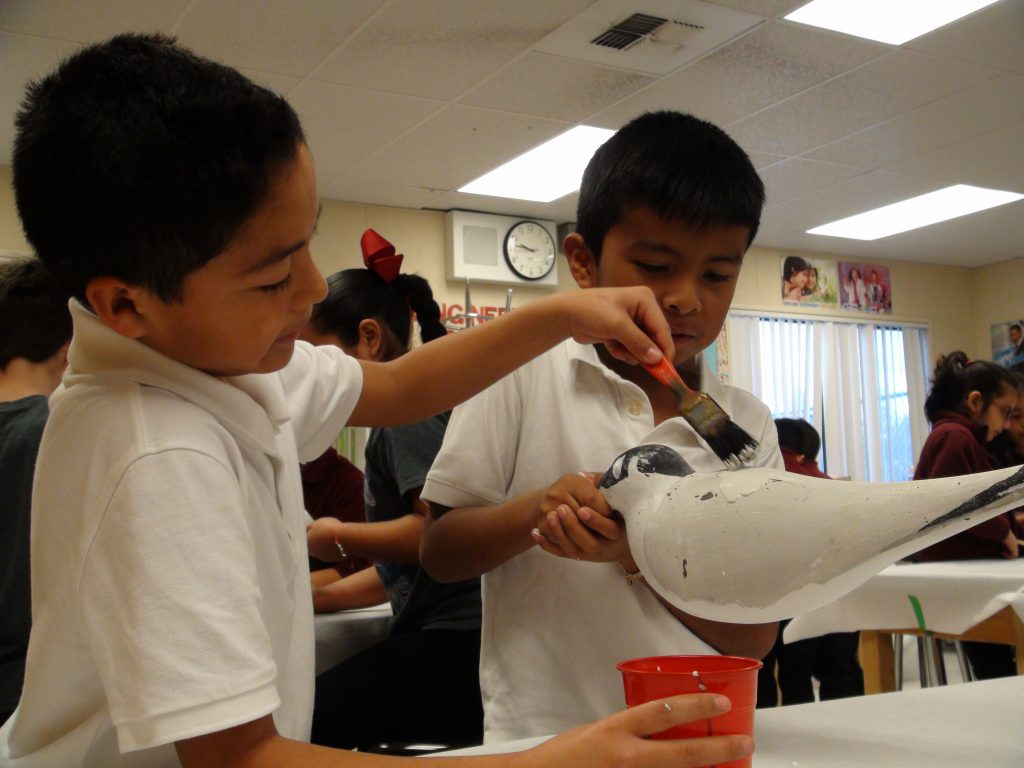

To lure Caspian terns down from the sky to Don Edwards, USGS biologists arrayed more than 500 tern decoys, some of which were painted by local students. They also installed Murremaid Music Boxes with MP3 Players that jam Caspian tern calls.

This is the third and final year of the social attraction and monitoring phase of the project. The Corps expects more terns to take a liking to Don Edwards because of the fish banquet, and because the species has a history of nesting in the South Bay. The Corps’ goal is 100 to 1,500 breeding pairs. “There’s still time for more Caspian terns to find these islands,” said Schmidt.

If the terns show up and expand in numbers like they did in the Columbia River estuary, what then? Project managers say that the nesting colonies aren’t likely to negatively impact endangered salmonids here. An earlier study by Oregon State University found that salmonids don’t factor significantly in the diet of Caspian terns nesting in South San Francisco Bay.

The pull-push strategy of this management plan has yet to play out. Meanwhile, it’s worth noting that both salmonids and Caspian terns travel great distances and return home with site fidelity. They have that in common. But one can fly over the dams and fish ladders of the Columbia River, and the other cannot, a fact that contributes to one being endangered and not the other. Salmonids also support a large amount of the economy in Oregon and Washington. Terns do not. These factors play into the push and pull decisions that people make about wildlife.

Contact: C. Alex Hartman;

David A. Trachtenberg;

Genie Moore; Cheryl Strong

Related Links

Caspian Tern Nesting Science Paper, USGS 2017

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.