For two cold clear days in February, scientists, engineers, and other specialists from all three North American coasts gathered at the Oakland Airport Hilton, in what a local speaker called “the least interesting part of Oakland,” for the second national Living Shorelines Technology Transfer Workshop. The event, co-sponsored by Restore America’s Estuaries, the California Coastal Conservancy, and Save the Bay, featured talks and interactive sessions on this emerging approach to coastal protection that went well beyond technology. Referred to by some practitioners as “soft shorelines” or “green shorelines,” living shorelines projects deploy a range of environmentally friendly alternatives to armoring shores against rising seas and stronger storm surges, along a gray-to-green continuum.

As speakers described challenges encountered and progress made from the San Juan Islands to North Carolina’s New River estuary, distinct regional flavors emerged. “We all live in unique systems,” Hugh Shipman of the Washington State Department of Ecology noted. East and Gulf Coast living shorelines projects have been hailed as models, but their lessons may not translate to the Pacific Coast, where significant regional differences also surfaced. San Francisco Bay and Puget Sound, the coast’s two great urbanized estuaries, have much in common—hipster scenes, high-tech fortunes, coffee cults, earthquake anxiety—but, as Shipman and two other Washington State panelists made clear, they diverge in the opportunities and constraints they present for living shoreline initiatives.

For one thing, Puget Sound, unlike San Francisco Bay, is a glacial fjord system. Its waters are deep, its shores mostly steep and its beaches narrow, with some river delta marshland on the east side. The tidal amplitude is greater and wave energy is higher. Sediment moves around mainly within the system rather than down from an interior watershed. Coarse sediment and large pieces of wood are key components. Aquatic vegetation is different; cordgrass, for example, is absent.

Armoring this shoreline has had a suite of impacts such the loss of upper beach habitat, reduction in sediment supply, and disruption of continuity between marine and upland forest ecosystems. “Shoreline erosion is an important ecosystem process, driving ecological functions,” Shipman explained. Promoted by state and local regulations, the goal of what Washingtonians prefer to call soft shorelines is to reduce erosion while maintaining those functions. The state’s administrative code requires property owners to demonstrate that soft approaches won’t work before permitting hard options.

“There’s no single template, but a tool box,” Shipman said. Small-scale beach nourishment has been the most commonly used tool. Backshore (not beach) planting and the structural use of large wood are also part of the repertoire, with multiple techniques and hybrid designs in play. Supported by federal and state funding, some beaches have been restored by removing hardened erosion control structures.

Shipman acknowledged mixed results: “Some projects have worked very poorly. Some haven’t dealt with underlying causes of erosion like the sediment deficit.” He also points to “a dearth of good contractor and designer experience” and a lack of long-term study and follow-up: “There’s been more monitoring done than evaluation and synthesis.”

Limited confidence in the soft shore approach among property owners remains a constraint. However, other projects have performed well in the short run. “We’re all thinking about how sea level rise will change the world enormously,” Shipman said. “Our projects are going to look different. Long-term resilience needs space and sediment.”

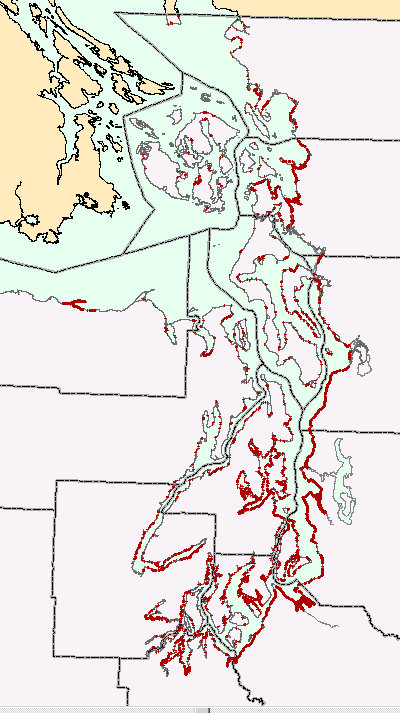

Almost a third of Puget Sound’s 2,500 miles of shoreline is already armored; living shorelines advocates want to keep that proportion from increasing.

That means getting buy-in from shoreline landowners. According to Nicole Faghin of Washington Sea Grant, half of the sound’s shoreline properties are the sites of single-family homes, whose owners are anxious to protect their beaches and may be dubious about novel approaches.

“Homeowners are concerned about erosion and the cost of having to do something, and terrified of the permit process,” she said, summarizing survey results. Faghin sees social marketing as a way of making this target audience more receptive to living shorelines, with “Shore Friendly” branding, LEED-inspired certification programs, and “homeowner ambassadors” for peer-to-peer credibility. That also goes for key influencers like contractors, who can be offered specialty certification and preferred provider lists, and realtors, who may respond to continuing education credits. Streamlined permitting is part of the incentive mix.

Puget Sound also has shoreline communities with no exact Bay Area parallel. Todd Woodard described his beach restoration work with the Samish Indian Nation’s Department of Natural Resources, whose Samish name translates as “House of Watching Over All the Territory.” “There’s a deep cultural connection to the sea,” Woodard said. “There’s a Samish saying: ‘When the tide is out, the table is set.’ It’s impossible to distinguish cultural from natural resources.”

Woodward’s projects with the Samish at Weaverling Spit near Anacortes have addressed the recovery of shellfish and forage fish habitat and access for annual canoe festivals as well as winter storm effects. He’s consulted traditional ecological knowledge to inform shoreline planting: “We’ve talked to local folks about how their culture used plants, tried to look outside the landscapers’ standard menu.” Local nurseries have been propagating culturally important native plants for restoration projects.

Katharyn Boyer of San Francisco State University’s Estuary & Ocean Science Center, with deep experience in intertidal habitat restoration, sees differences on both policy and operational levels between Puget Sound and the Bay. Unlike Washington and some Gulf and East Coast states, California has no state or regional policy requirement for living shorelines to be considered before implementing harder alternatives.

Local projects have done less with coarse sediment and woody material, but that may be changing. Pilot projects at San Francisco’s Pier 94 and Aramburu Island in Richardson Bay have already used coarse sediment. Aramburu also incorporates wooden groins. “There are other places where woody material would work, with placement and degree of anchoring dependent on the direction of the waves hitting the shore,” says Boyer. Properly placed, it would help promote sediment accumulation. The San Francisco Estuary Institute is involved in developing operational guidelines. She also notes that unlike San Francisco Bay, Washington is not looking at vegetation to protect shorelines.

Ownership of shoreline land and subtidal acreage is another consideration. “Coordination here may be easier with larger parcels and fewer owners,” Boyers says, contrasting Puget Sound’s many private shoreline properties with the huge stretches of Bayshore in the East Bay Regional Park system. A complication in San Francisco Bay is the pattern of private ownership of subtidal parcels. “It’s not necessarily the same landowners as at the shore’s edge,” she adds—a mosaic of corporate, nonprofit, and individually owned lands. “Marin County Open Space owns parcels out in the middle of Corte Madera Bay.” Boyer’s oyster-reef project off San Rafael is sited on a Nature Conservancy parcel; expanding it would run up against private ownership.

Events like the Oakland workshop, with additional sessions addressing outreach, funding, permitting, and other areas, foster the exchange of ideas and techniques among regions. Boyer says it has already inspired further discussion with folks in Washington State: “There’s more we can learn from them.”

Washington Shore Friendly Program

Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project

Living Shorelines Project, State Coastal Conservancy

Pier 94 Restoration, San Francisco

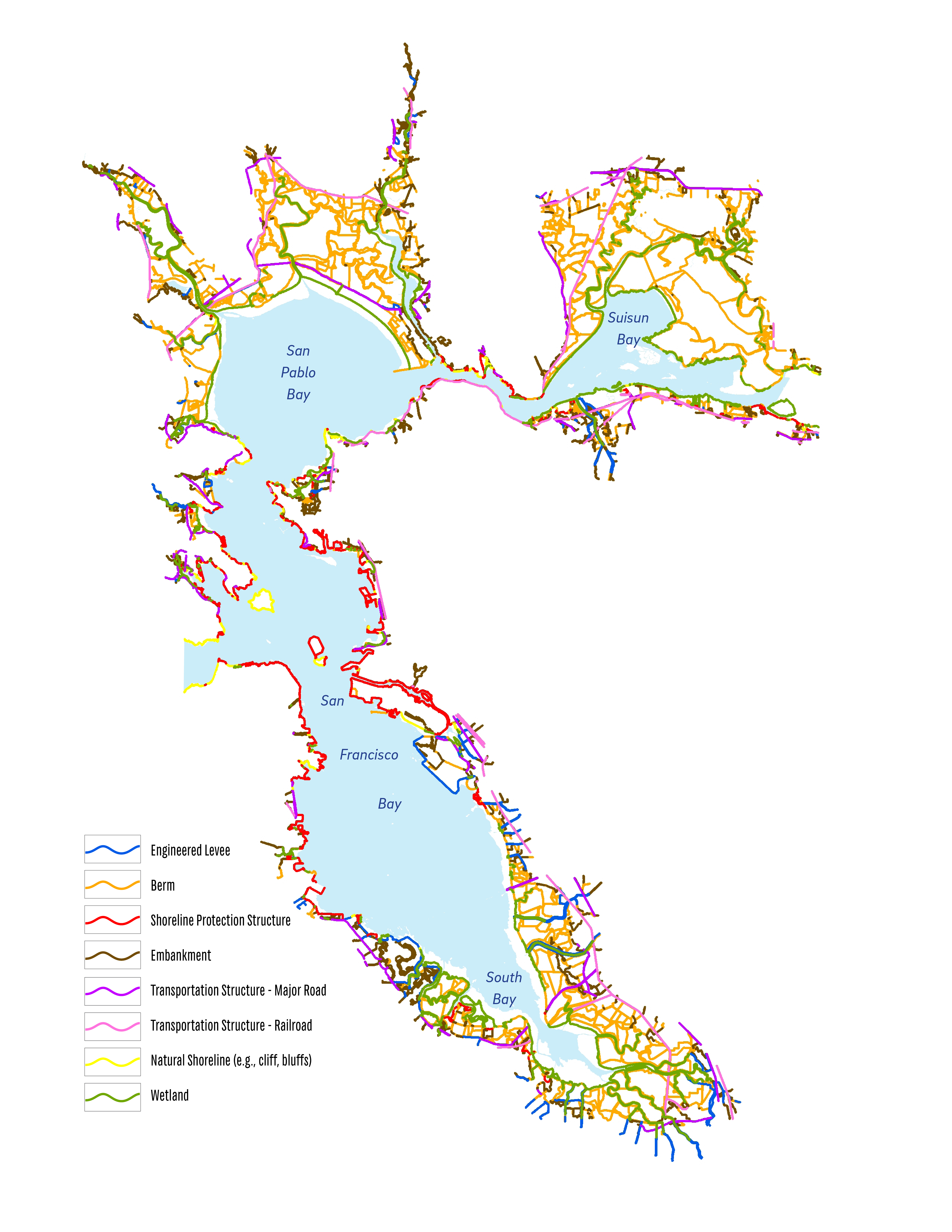

San Francisco Bayshore Infrastructure Inventory

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.