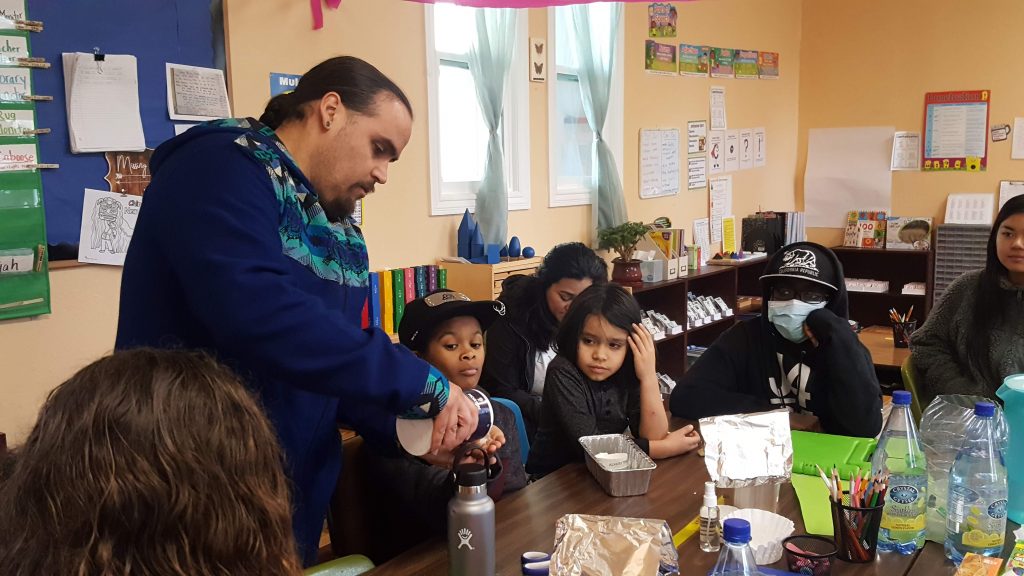

In a bright classroom in the hills of East Oakland, youth huddle in small groups building miniature rain-catchment models. Birdhouses serve as the base for a catchment system composed of a foil gutter, a straw pipe, and a Dixie cup rain barrel. Spritzes of water from a spray bottle generate rain-like condensation, which trickles through the system into the barrel.

The eight middle schoolers gathered on this chilly Saturday morning are participating in a youth social-media ambassador training organized by a climate-readiness program called Mycelium Youth Network. In a few weeks’ time, they will build a life-size rain catchment system here at Pear Tree Elementary School.

Lil Milagro Henriquez founded Mycelium Youth Network in late 2017, while fires engulfed California. Mycelium was born “out of deep anxiety” from confronting the gravity of climate change, she says. Henriquez, who had just given birth, recalls wondering, “How are we going to survive this? What kind of world am I leaving for my children?”

At the training day, black and brown faces fill the room, and the educators are predominantly Native. Henriquez believes that “from these communities will emerge the practices that will save us and allow us to thrive,” she says. “I want the practices in the classroom to be focused on this reality.”

At the center of the six-week Mycelium curriculum is a segment called Water is Life, in which students learn practical skills. Ben Schleffar, a garden educator trained in traditional Native American techniques, teaches students how to follow plants to sources of fresh water and to identify native plants with medicinal properties. Dani Ahuicapahtzin Cornejo leads lessons on purifying water in a disaster and building a rainwater catchment system. He teaches that humans are inside of nature rather than apart from it. “We are water beings, we are part of a water cycle,” he says.

Henriquez created Mycelium after a search for disaster-preparedness courses yielded few climate-readiness programs and scant resources for people in her community. She found even fewer initiatives specifically concerned with youth like the students she worked with at her school. Henriquez is the Director of Community Organizing at Roses in Concrete Community School in East Oakland. For 17 years, she has been an organizer for various causes including rights for domestic workers and janitors. She brought that organizer mentality to creating Mycelium: “Let me change what’s happening and figure out how to make it better.”

There’s no doubt the prospect of climate change inspires both hope and fear. This January, Mycelium Youth Network was included in a report titled “Preparing People on the West Coast for Climate Change,” authored by the International Transformational Resilience Coalition (ITRC). According to the ITRC, human psychosocial resilience is vital to climate adaptation, but it receives less support and funding than initatives geared toward infrastructural or economic resilience. Human resilience programs like Mycelium are an investment — they prepare people to deal with the trauma and stress of disasters. They also address everyday trauma that easily gets normalized.

Although the rest of the school was empty during the rain catchment exercise, our classroom felt like a small community center. Relatives and guest educators sat amongst the youth to listen to presentations, or stopped by to contribute to the potluck lunch. Ayako Nagano, an attorney and community organizer, kicked off the day with a social-media ambassador workshop that covered everything from blogging to photography. The middle schoolers moved about the classroom, snapping shots of each other. Mosiah modeled for his partner by busting out gravity-defying dance moves. Regardless of the medium, “It’s your perspective we want to know,” Nagano told the youth.

This perspective is aware that people of color and low-income communities live at the frontlines of climate change. Henriquez describes how in their Oakland 94601 zip code, there is already lead in the water, particulate matter in the air, and little access to healthy organic food. Disasters and added stresses from climate change will exacerbate existing challenges. Her students are already “disproportionately targeted, and they know it,” she says. At the same time, she pushes back against media portrayals she thinks only highlight what is missing or problematic in her community. “We don’t focus on the resilience that’s already there,” she says.

Resilience usually calls upon diverse skills. Mycelium brings together youth participatory action research, disaster preparedness, urban and wilderness survival, ecological sustainability, and visionary imaginings. Activities include a “walk your block” exercise to identify medicinal and sacred plants as well as lessons on how to mobilize an emergency bag and family plan for when disaster strikes. As Henriquez remarks affectionately, it’s a dynamic “hodgepodge.” She wants to ensure the curriculum is responsive to the community’s needs. “We just had a wildfire, so how do we make an air purification system? I want it to shift as the world shifts,” she says.

During trauma and crisis people become individualistic, which works against them. “Our fight or flight reaction gets activated and we lose our executive functions, our decision-making skills,” says Nagano. Mycelium combats this panic by teaching students key skills in advance — like how to procure potable water — and through lessons on working collectively.

Those skills have come to Henriquez organically. When she began building Mycelium from scratch, she looked outward into her community. “When I don’t know, I go to people who do know,” she explains simply. She connected with Mycelium’s educators and board members at climate adaptation forums, at Native American resource centers, through relatives, and in her school garden. The resulting Mycelium program “integrates eco-social justice, indigenous pedagogy, and water engineering,” says Pablo K. Cornejo, a civil engineering professor at California State University at Chico who consulted on the curriculum.

While Mycelium takes disaster-readiness seriously, exploring what lays beyond survival is also important. “How do we go from a place of survival to thriving in a climate challenged world?” says Henriquez. Mycelium encourages the youth to imagine radically. “We always want to keep the imagination piece in there: How are we thinking about the world together in a new way?”

Mycelium prompts its students to write speculative fiction and envision a world they want to see. Sana, a Mycelium student, is writing a story that explores “overcoming dystopian conditions, sustainability, and understanding how people created the dystopia.” Sana wills her characters to overcome stacked odds; she “likes dystopias but hates when everybody dies at the end.” As the author, she wields the power to write her characters — and her community — out of harm’s way.

“What’s beautiful about youth is that they think outside of the box — they are visionary,” says Henriquez.

The January ITRC report described how resilient people are better able to make sustainable lifestyle changes that will lessen their carbon footprint. The ITRC characterizes this brand of resilience as “transformational” because it turns a challenge into an opportunity, and makes people feel empowered rather than helpless.

“If we don’t change our minds, the physicality of our world won’t change,” says Nagano. Henriquez believes surviving climate change will take the whole village — “from the ingenuity and creativity of youth, to the knowledge and experience of adults and elders, to the wisdom and traditions of our ancestors.”

At the Mycelium workshop day, Henriquez sat amongst the youth. She listened to the educators and piped in occasionally, but mostly watched the workshop unfold. She had no need to assume center stage because she had already done her part: organizing the network to support the next generation of collective leadership.

“The youth should be the leaders!” Henriquez exclaims. “They open us all up to the possibility of the impossible. Within Indigenous circles, we often say, we are our ancestors’ wildest dreams. No one embodies that more than youth.”

Photos: Annakai Hayakawa Geshlider