Morning at Suisun Marsh is a living watercolor with a soundtrack. Miles of tule and pickleweed populate the foreground, split by canals glinting silver from the sun. In May, the hills undulate across the northern boundary in classic California gold. A red-tailed hawk’s iconic hoarse screech punctuates the insectine buzz as it takes off from a powerline. At 7:40 AM, it’s already 72 degrees and there’s no trace of a breeze.

I’ve come to visit the Marsh from downtown Oakland seeking to learn from biologists, hunters, and land managers what’s at stake in the myriad battles with rising seas, worsening drought, and, especially, encroaching invasive species and what makes it such a singular, attractive landscape.

Indeed, the pastoral foreground is cast in stark relief by the imposing steelworks surrounding the periphery. To the south, the towering Pittsburgh stacks loom on the horizon. To the west, refineries in Martinez and Benicia puff miniature cumulus into an otherwise crystal-clear blue sky. In a kind of call-and-response, the hawk’s cry is echoed by a whistle from Amtrak’s Capitol Corridor train, hurtling across the western marsh towards Fairfield and on to Sacramento.

A cursory glance suggests a sort of unaltered refuge, but Suisun Marsh is as much a human construction as the steelworks that surround it, as improbable as the railroad that traverses it. Comprising dikes and levees, floodgates and canals, the ecological paradise that serves as an indispensable stop on the Pacific Flyway is thoroughly human-made.

At 180 square miles, the Marsh is often called the largest brackish marsh in North America (this is debatable but it is certainly the largest in California). Unlike at many ecological preserves across the continent, more than 80% of Suisun’s vast swath of land is managed by private interests. Of that private land, the majority is managed for waterfowl habitat and hunting interests. Each of these landowners and hunting clubs has its own priorities and concerns. A levee raised along a contrived property line divides two utterly different ecosystems, fostered by the interests of the respective landowners.

The Marsh as we know it is buttressed against reduced freshwater input from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and a rising sea, but vulnerable to encroaching invasive species that thrive in an ecosystem lacking the natural checks against their rampant spread.

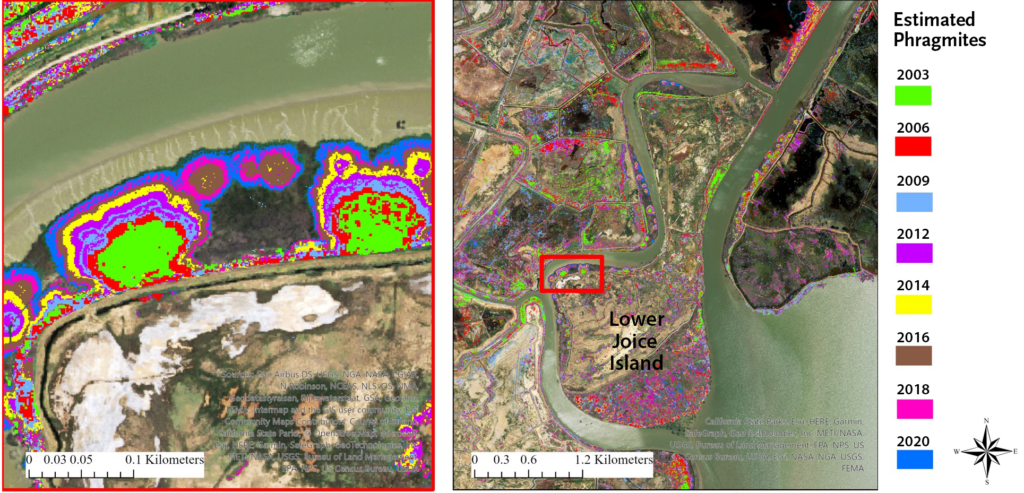

One such species, Phragmites australis, or the common reed, has entrenched itself in Suisun Marsh, and threatens to dominate the habitat the hunting clubs have worked hard to preserve for Pacific Flyway ducks and waterfowl. While Phragmites is a well understood problem and control methods have been implemented, its rate of spread has increased in the last 20 years. Effective control requires an approach as novel as Suisun’s own land-management mosaic.

Adrienne Ernst parks her tan SUV next to an old hunting shelter and hauls out a rectangular sled loaded with native plants. Her research associates Gabe Rodkey and Jason Hagani follow in a UTV (Utility Terrain Vehicle) and, after assessing the plant inventory, strap the sled to it. Following Ernst’s recommendation, I’ve come dressed in waders. The research team is wearing the duck-hunting kind, and my borrowed ‘90s-era neoprene trout-fishing waders would offer some comfort in the frigid waters of alpine meltwater, but are a sticky, sweaty, miserable mess in the Suisun heat.

“And we’re off like a herd of turtles,” quips Rodkey as he and I follow Ernst’s UTV on foot. After passing between head-high plants, the road opens up and follows the riprap levee marking the southern terminus of Suisun Marsh.

Rodkey points out a stand of Phragmites where they are conducting their research. Like with many invasive plants, Phragmites looks right at home in its assumed habitat. It’s a tall, woody reed with long leaves curling downward and a feathery, duster-like tip. Up close, though, the reed’s utter ecological dominance is more apparent. It grows in such density that other native plants, including those that wintering birds rely on for food, can’t compete. When an individual reed goes to seed, it leaves behind a brittle stalk that can puncture skin and impede wildlife travel.

At this particular stand, the research team had cleared a section of reed and planted a representative sample of native plants in a grid framework several months ago. They’ve returned today to check the plants’ progress.

“Things seem to be growing pretty well,” says Hagani. “I mean, the phrag is too, but so is the other stuff.” New Phragmites shoots have already outpaced the new plantings, but rather than composing a homogenous stand, they’re interspersed with the others. “I’ll take it,” says Ernst.

For each block like this one, the researchers have applied three different “treatments,” or arrangements of native plants. One features aggressive species that show resistance to invasion, one is drought- and salt-tolerant species, and the final is a selection of species preferred by the Marsh’s waterfowl.

Ernst’s past work has looked at tallgrass prairie ecosystems and how different types of plant diversity affect resistance to invasion. Her postdoctoral research, under the supervision of Phragmites expert Karin Kettenring at Utah University, is one component of a larger socio-ecological study on Phragmites in Suisun overseen by John Takekawa, operations manager of the Suisun Resource Conservation District.

“Despite efforts to control, it has expanded,” says Takekawa. “The part of why, where, and how is where we’re trying to provide a historical review.” More than a simple collection of native plant and invasive Phragmites data, the project will also look into the cultural background of land management that affects invasive species control.

Ernst’s research takes place at sites both public and private across a representative sample of the Marsh, and her findings will be used to inform plant management practices – but it may not lead to a simple, easily implemented solution. “There’s a lot of heterogeneity in vegetation and land usage,” she explains of the Marsh’s complex ecology. “All of our sites look very different.”

So not only may there not be one simple plant-management plan that will work across the entirety of the landscape, but it might also be difficult to find agreement between, say, a landowner concerned about salinity intrusion and a landowner concerned about other, newer invasives.

At a second site in the south of Grizzly Island, Ernst and Hagani notice the cleared-out plot has a new problem. “This looks like the mother,” says Hagani, who hefts a large, tangled tumbleweed and removes it from the plot. As the bramble tumbled across the marsh, a spread of waxy-green Russian thistle has taken root in its wake.

Russian thistle is a newer invasive species on the marsh and may pose an even greater risk of degrading habitats than Phragmites, but it’s challenging and costly to manage. And for a private landowner, like Kent Hansen of the Goodyear Land Management Company, whose hunting club foots the bill of managing their wetlands parcel every year, it can often come down to an either-or decision.

Dressed in denim, a ballcap, and a blue pinstripe button-down shirt, Hansen invites me into the Goodyear clubhouse with a firm handshake and an easy, welcoming demeanor. Decorating the walls are taxidermied ducks and historical maps and newspaper articles. He offers me a sports drink from the clubhouse fridge and talks a bit about the club’s history and amenities and his plan for the day.

Climbing into Hansen’s own UTV, which seems to be the preferred vehicle for transiting the rugged Suisun Marsh landscape, we tour the Goodyear property.

Private duck-hunting clubs are central to Suisun’s present role as an ecological refuge. Hunting on the marsh survived through attempted land reclamation (farming failed because of salt intrusion; mining interests didn’t pan out) and territorial battles between late-19th-century clubs that local press covered with the same fervor normally reserved for European land wars.

Thanks in large part to the popularity of hunting and Suisun Marsh’s proximity to urban centers, San Francisco’s high society took on the lion’s share of the costs associated with maintaining good hunting habitat, including both land management and legal battles with conflicting interests.

For example, when railroad moguls in the late 19th century planned to shorten the western end of the transcontinental railroad by cutting out Vallejo, they chose a route from Fairfield to Benicia, cutting through Suisun Marsh, rather than build the connection on the bedrock between Cordelia and Benicia, where Interstate 680 currently runs. Some of the oldest of the Marsh’s private clubs are situated directly adjacent to this railroad, which took nearly 50 years to build and rebuild as it sunk into the marsh.

Born to Montana ranchers, Hansen doesn’t appear to have much in common with those urban uppercrusters of hunting yore, but he recognizes the same financial challenges of managing attractive waterfowl habitat. “It’s a rich man’s game,” he says.

Goodyear Land Development Company owes its name to an old mining claim, but, when surveying the property with Hansen, it struck me as curiously apt for a duck hunting club. While the hunting season is confined to only a few months a year (which the clubs further restrict to two or three days per week by voluntary historical precedent), the land management is year-round.

Goodyear’s property, which is managed for puddle ducks like northern pintail and green-winged teal, is mostly dry in May. Hansen’s group spends $25,000 to $30,000 on “ground maintenance” each year, which includes tasks like spraying invasive plants, abating mosquitos, and “discing,” a practice that turns over plots of dirt to allow more diverse assortments of waterfowl-friendly plants to grow (Hansen is particularly fond of grass buttons, whose black seeds he calls “caviar for ducks”).

After each hunting season, the soil has to be “leached” of salt through a series of flood and drain cycles. A new floodgate costs $35,000, and one needs to be replaced every year. The swales that drain each field fill up with sediment and need to be dug out periodically to the tune of $25,000.

All of this is to say that land management comes at a steep cost, one that Takekawa, whose Resource Conservation District works closely with the Marsh landowners, is keenly aware of: “You have to decide where to put those funds,” he says of the many either-or decisions landowners have to make with their budget each year. “That can be a difficult choice to make.”

At one point on my Goodyear tour, Hansen’s ATV rolls up along a levee at his southern property line, and we’re presented with a pretty demonstrative juxtaposition. While Goodyear is drained and dry this time of year, the property across its southern border, which is managed for mallards, is flooded, both with water and Phragmites.

Hansen explains that they have a different “water idea,” or that they manage their water to attract their preferred species, and different water ideas apparently carry different problems. Goodyear has Phragmites pretty well under control and is much more concerned about Russian thistle. This land to the south has a keen Phragmites problem, however, and according to Hansen, the only real solution, due to problems of access and spraying herbicides in water, is to manage it with controlled burns.

The either-or decisions landowners make with their money are further compounded by the fact that management decisions are not made in a vacuum. “If one side of a levee is doing a good job [controlling Phragmites] and the other isn’t, it can return to the areas where people are trying to control it,” says Takekawa. “Everyone needs to work together.”

Coordinating a consensus in a management group the size as it is in Suisun presents a problem of collective action, and one that Takekawa’s colleagues in the larger Phragmites project, backed by the Delta Stewardship Council, are working on. Richelle Tanner, an ecophysiologist and science communicator, has looked into the data of how science is communicated to the public and is building a strategy for communicating the threat of Phragmites from the Suisun Resource Conservation District to local landowners.

“We’ve noticed that there is very little top-down communication about coordinated control of the species,” says Tanner, and “there aren’t many communication methods for landowners right next to each other.”

Tanner’s work uses environmental psychology and linguistics to build an evidence-based strategy for communication around Phragmites that can serve as the framework for disseminating a coordinated control plan. “There is a set of cultural values that many people share in a specific stakeholder group,” she explains of her strategy. “You can tap into that sense of community and trust if you use a cultural value. You can get people to take in info in a less biased way.”

Tanner offers an example: In a survey, she asked participants to read a few versions of a statement that defined “control measures” and asked them to rate how well they understood it and how it made them feel. The first one used language like “crowd control” and “crowd out their neighbors;” the second used “vaccination” and “difficult for the heart of the ecosystem to keep pumping.” The third described control measures as “used by everyday people when they weed” and “can help wetlands and vegetable gardens in the same way.”

If you felt the most positive emotional response to the third statement, then you’re in the same camp as the surveyed stakeholders, landowners, and other participants. Tanner believes data collected in this fashion can help guide the efforts to present a Phragmites plan that doesn’t alienate landowners or build mistrust and allow a plan to move forward with Marsh-wide consensus.

Tanner’s research is less about finding the one “golden ticket” solution that solves the Phragmites problem in Suisun Marsh, and more about finding one that works for the diverse interests and perspectives of the many landowners. “There isn’t one solution to anything,” she says. “We just need to make sure that all the different solutions can work together to create a strong, resilient ecosystem.”

The book Suisun Marsh: Ecological History and Possible Futures, introduces the idea of the “novel ecosystem,” or an ecosystem owing its current state to anthropogenic change and without an historical precedent to look to for guidance on how to imagine its future. Takekawa agrees with this assessment of the Marsh.

“Bringing back the time before people is not gonna happen,” says Takekawa. “We aren’t going to let Sacramento flood, we aren’t going to tear down the dams in the Sierras, many things are changed that cannot be changed back.” Similarly, he feels that a future without Phragmites isn’t a realistic expectation.

A “Phragmites sea” (a possible end state where the Marsh becomes a single-plant monoculture) might not even be the worst outcome imaginable. Takekawa notes that the plant is valuable for its ability to sequester carbon, and Tanner notes that research shows that the reed is a good home for aquatic invertebrates which may in turn attract a new group of birds to the Marsh.

Suisun Marsh identifies how competing perspectives complicate Marsh management going forward: “The problem, of course, is that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, so one person’s positive outcomes is another person’s bad dreams. Therefore, debate and dialogue among those who care about the Marsh are vital to looking forward with intention.” In other words, if my vision of a marsh was as a haven for aquatic invertebrates, who’s to say Phragmites is such an enduring problem?

Still, “In most people’s view, a marsh managed for species diversity is much preferred over a Phragmites sea,” Takekawa notes. It’s not a preferred outcome because too many people are too invested in keeping the Marsh headed in the direction started by the decades of work done by those who frequent it most.

“I think that’s the perspective we have for this area.” says Takekawa. “It’s novel, and that’s okay. What values do we get out of it society-wide, and what things make it so it’s still an enriching part of the natural ecosystem?”

Before leaving Goodyear, I shared the novel ecosystem idea with Hansen. Hunters like him have some concerns about a future with easier-to-find sources of entertainment and fewer and fewer young people taking up hunting, but he finds optimism in the work done by the Suisun Resource Conservation District, and by the duck hunters and private landowners who have helped make the Marsh such a valuable stop along the Pacific Flyway.

“People think of the marsh as this big old mushy place, but that isn’t true at all,” he says, gazing out towards Rio Vista and the windmills hanging on the eastern horizon. “You should come back sometime for a sunrise. They’re really spectacular.”

Top image: Adrienne Ernst among the Phragmites. Photo: Michael Adamson.

Related Estuary Posts

Other Links

Suisun Marsh: An Ecological History and Possible Futures, UC Press