After decades of restoration, recent Chinook salmon runs in Putah Creek have reached 1,800, producing young that swim toward the ocean by the tens of thousands. But, says Putah Creek streamkeeper Max Stevenson, this growing population still faces considerable obstacles.

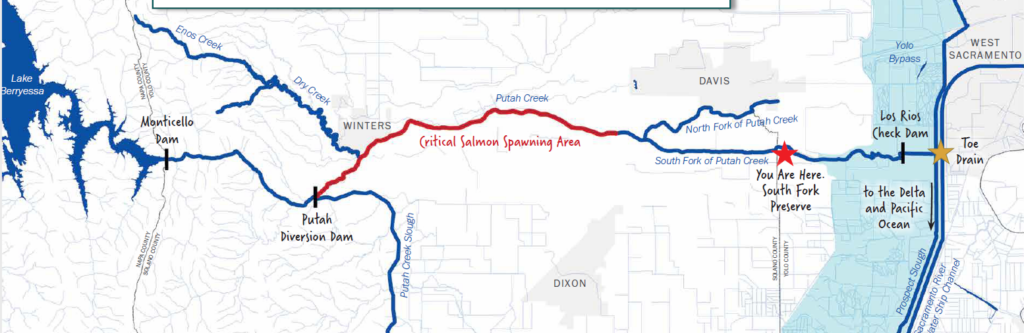

Putah Creek flows from headwaters in the North Coast Ranges to the Toe Drain of the Yolo Bypass, and was dammed near Winters in the 1950s to divert water for Solano County. Salmon began coming to the creek after settlement of a lawsuit in the year 2000 that stipulated releasing water for fish as well as optimizing spawning grounds.

Salmon need loose gravel to dig spawning pits, or redds, that are up to six feet across. “They flop over and slap cobbles as big as six inches with the side of their body,” says Stevenson, who the Solano County Water Agency hired almost exactly a year ago as streamkeeper to protect and restore Putah Creek. After spawning, salmon fill the pits back up with gravel to hide their bright-orange eggs from predators.

Dams keep new gravel from tumbling down Putah Creek, and old gravel hardens over time as the space between cobbles fills with fine sediment, forming a thick, cement-like crust on the creek bed. “You can walk on it and not sink in,” Stevenson says. To loosen the gravel for salmon, the restoration team “fluffs it up with excavators.”

Last year, the team also tried something new. They added 80 tons of gravel below the pedestrian bridge in Winters and were almost immediately rewarded. “There were 15 redds!” Stevenson says. Salmon can lay thousands of eggs in a redd.

Spawning grounds are not enough to support a self-sustaining population of salmon, however. These migratory fish also need unrestricted passage. “You can create gold-star, top of the line, Cadillac salmon habitat but it doesn’t matter if they can’t get there,” Stevenson says. “There’s wonderful upstream habitat near Winters, but below I-80 hasn’t seen the love yet.”

The lower reaches of Putah Creek between I-80 and the Toe Drain are like an obstacle course, sporting several barriers to fish migration. One barrier, a pair of culverts under County Road 106a, has a temporary fix. “The culverts are way too high for salmon to jump,” Stevenson says. So the restoration team worked with the farmer who owns the land to install a new fish-friendly culvert.

Stevenson is excited that they used culvert design software, called FishXing, to optimize the size and placement of the new pipe for salmon. From a fish point of view, culverts are trouble when they are out of reach or when water comes through too fast to swim against. The restoration crew embedded the bottom of the new, but temporary, culvert in the stream bed, both making it accessible and slowing the water.

Two miles downstream of Road 106a lies another, more significant barrier to fish passage. This is the Los Rios Check Dam, which is more than 12 feet high and is opened and closed by manually removing and replacing heavy wooden boards. “As soon as the check dam was opened in November last year, 64 salmon shot through the new Road 106a culvert in two hours,” Stevenson says. The fish-friendly culvert is something of a bandaid, though, because it could get washed out in the next storm.

For a permanent solution to both barriers, Stevenson envisions creating bypasses to allow year-round fish passage. A 1,600-foot channel around the check dam and a small bridge-like creek crossing for Road 106a would each cost less than $1 million. Stevenson also hopes for a solution to a third salmon barrier: the Lisbon Weir, which is made of rocks and spans the 100-foot width of the Toe Drain.

Stevenson’s big dream is to realign Putah Creek below I-80 completely. “The lower third is human-made,” he says. “It was dug out in the 1870s to relieve flooding and is as straight as an arrow.” Realignment would sidestep all three fish barriers at a cost of $20 to $40 million.

While the restoration team collaborates with many of the private landowners along the creek, sometimes it just doesn’t work out. “Landowners worry about ATV trespassing and equipment theft in the park-like areas created by restoration,” Stevenson says. “They don’t always want to invite that.”

Plans for rerouting lower Putah Creek have been drawn up. The beauty is that the bypasses to Lisbon Weir, the Los Rios Check Dam, and Road 106a would all be built entirely on public land, which would simplify the process.

“The ten miles near Winters are great for salmon,” Stevenson says. “But these fish have to swim another 100 miles between Putah Creek and the ocean—we need to connect them.”

Top Image: Los Rios Check Dam open for fish passage. Photo: Max Stevenson