Restoration is a powerful concept. Physically it entails putting something back, making it right again; emotionally it requires hope for the future, a sense of something worth doing.

In the Estuary, restoration is no longer about recreating some pristine ecosystem that once was. The vast marshes that carpeted the Delta and circled the Bay before Europeans arrived out West are long gone; the great rivers spilling fresh water and salmon downstream are a shadow of their former selves; the myriad creeks and sloughs offering migratory paths and habitats for so many estuarine creatures are now laced with obstacles and lined with concrete.

But for some time now, the call to restoration work has been growing. People in all walks of life have answered the call – scientists, engineers, farmers, activists, politicians. Young people and families have gone out to pick up trash and plant natives. Bird buffs have gathered every year to count avian migrants overhead. Creek adopters have rebuilt eroding banks and carried steelhead around dams so they can reach spawning grounds.

A succession of government programs have committed and recommitted to saving the Delta, the endangered, the baylands, water quality, and more — urged on by the champions of the environment. Politics often intervene in reaching ambitious goals but somehow most people still support ecosystem restoration in some form. It feels good.

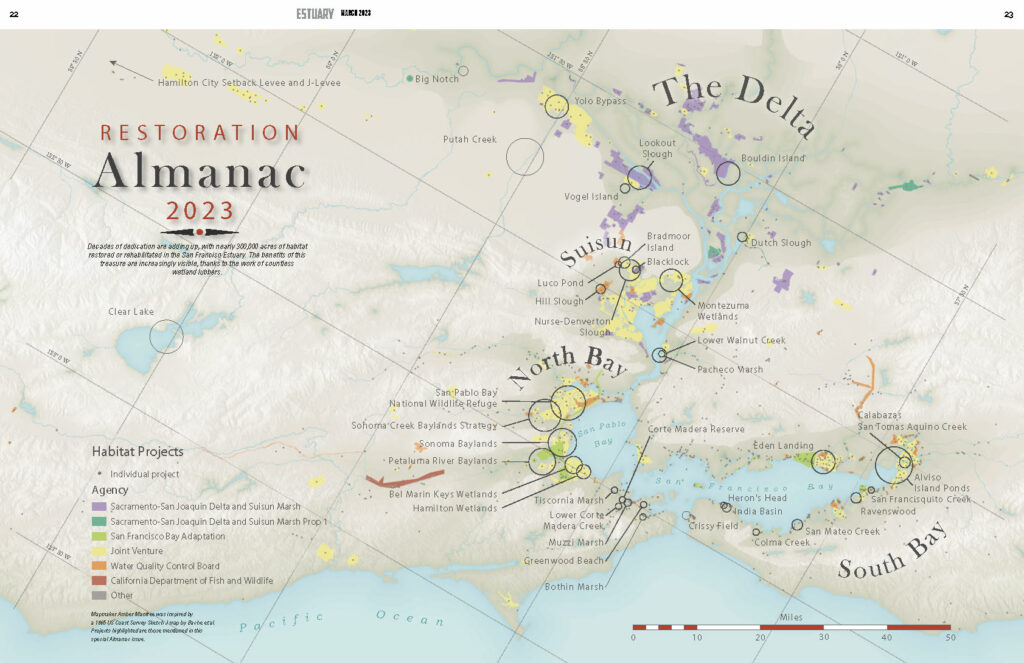

In this special Almanac of Restoration issue of Estuary News, we celebrate restoration in all its forms and sample projects of every kind. We review a few ways in which we are measuring our progress: did the birds and fish come back? And we delve deeper into some of the latest iterations of restoration, ranging from centering equity and nature-based design to combining flood control and habitat creation in multi-benefit projects. We also include stories representative of the different landscapes that make up our Estuary, starting high up in the watersheds with rivers, lakes and creeks, moving into the Delta and upper Estuary, and then exploring efforts all around San Francisco Bay. Finally, we offer some retrospective reflections — in story, audio and video — of the changes in our thinking over the decades since we decided, sometime way back when, to try to fix an ecosystem so altered, so remade, it is hard to imagine it healthy ever again. The field of restoration, here in our Estuary, reflects myriad fascinating nuances.

For myself, I was drawn to this work back in the early 1990s out of frustration. Not enough people seemed to be aware that we were fouling our nest. It was clear to me that if we kept polluting and destroying and paving and killing what was still wild or green that there wouldn’t be much left to sustain our own health.

Despite our nation’s strong environmental mandates, not enough of us have since made restoring our nest a priority. For myself, telling your stories in Estuary — revealing the heroism and wisdom of all your research, resource management, advocacy, and restoration efforts — has sustained me in this long battle for our future. But I think we all realize now just how royally we messed up. And how many problems remain to be solved.

My personal beat, as soon-to-be editor emeritus, has been quirky. For some reason, my favorite topics in these 30 years of storytelling have been sediment, mercury, and Giant Marsh. I began writing about sediment and dredging because no one else on our writing team would do it – boring! But it soon became the ubiquitous ingredient in almost every estuarine restoration story. Mercury – from our mining legacy and now everywhere in our air and water – challenged me with its shapeshifting complexity. It could be inert or toxic; it could lay around in the mud for centuries and then suddenly get disturbed and passed up the food chain; it could taint your bass filet or make you go crazy.

But in later writing years I settled on Giant Marsh for the reasons mentioned above. This project to restore the whole range of intertidal habitats – from subtidal eelgrass beds and oyster reefs to mudflats and salt marsh to upland transition zones — captured my imagination due to two things: the sheer difficulty of doing some of the restoration work in the sticky bay mud; and the ambition of it. Here was, and is, an example of how we can dream big about restoring our nest and then actually do it. As Roosevelt once said, and I can’t resist a minor edit for brevity: If it’s not hard, it’s not worth doing.

When I asked some of our restoration practitioners to share their views about restoration in audio many responded with eloquent reflections and insights. These responses are offered throughout this post in different forms. Some look back and some look forward. We tried for a mix of folk from younger and older generations. Together with the variety of voices in our 17 other stories, we hope our readers get a sense of the richness and variety of work to restore the Bay, Delta and watershed.

Steve Culbertson, Lead Scientist, Interagency Ecological Program

When wetland ecologists and planners were following up on the 2008 USFWS Biological Opinion regarding requirements to restore 8,000 acres of wetlands in the Delta and Suisun Marsh we became very excited at the prospect of adding so much additional acreage to the regional wetlands inventory. There was much pouring over of maps and ownerships of land in the Delta as we began imagining how and what wetlands could be restored where. Reality set in as we began to understand that finding that much suitable and available acreage (land at proper elevations in public ownership) was going to be a considerable challenge, aside from the daunting technical hurdles of constructing or “realizing” 8,000 restored acres of wetland habitat. What was particularly sobering as we pondered what effect all this additional wetland would have on the regional ecosystem more generally was the fact that even if we were to achieve the ambitious goal of 65,000 acres of additional restoration to our wetland inventories, we would be moving the needle regionally from 10% of existing historical wetlands to 12% of existing historical wetlands (as subsequently documented in the wonderful SFEI report “Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Historical Ecology Investigation: exploring pattern and process, 2012). How much of an effect on the estuarine biota should we really expect all this restoration to have, given the historical landscapes and how drastically the entire watershed has been altered? Would a few percentage points nearer to the historical precedent and evolutionary context prove to be at all meaningful? We really have yet to do enough or have waited long enough for the regional system to tell us the answer.

The October 2021 levee breach at the Lower Walnut Creek Restoration Project stands out as a milestone for restoration along the Contra Costa County shoreline. It was a huge project for our Flood Control District, but easily overshadowed by some of the other large restoration efforts around the bay. Early in the planning phase, we leaned hard into outreach via all the typical social media channels, and filmed a fun series of YouTube shorts called Lower Walnut Creek Adventures. We gave countless site tours and talked about “what we will build” and “the importance of the salt marsh harvest mouse.” We handed out custom posters to those that took a tour, and everyone seemed to really like the project. But ultimately it was hard to actually determine the public’s enthusiasm for the restoration work that we were working so hard to deliver. Of course, everyone in this relatively small world of restoration scientists, biologists, geomorphologists, and like-minded folks totally gets what we’re doing. But what about Jane Q. Public? What about those folks who need to vote for the funding, and write those letters to politicians to make sure restoration projects get done?

Once we were well into our construction season, I asked our contractor about setting an exact date for the levee breach, so we could invite some media, maybe get some cool photos and make it into some sort of event. I had attended a levee breach for another restoration project, and seen some on You Tube, and my expectations were pretty modest. When I sat down with staff from our project partner, John Muir Land Trust, my idea of a 20 person event quickly was supersized to 200 guests! The event went off without a hitch, and everyone left with a souvenir coffee mug. Most of the crowd that turned out were not restoration practitioners.

When the excavators roared to life and started to scoop away at the levee, it didn’t take long until water from Suisun Bay started to dramatically flow in. The energy level in the crowd was off the charts. With so many hoots, hollers and cheers, I was filled with a renewed hope that the desire to bring back habitat, to make resilient landscapes, and to better manage our wetland resources came from everyone in the crowd, not just us folks that do this for a living. It highlighted how many ‘normal’ people believe in the value of restoration and gave me optimism that Lower Walnut Creek wasn’t just something special, but rather a Contra Costa milestone that bodes well for restoration projects to come.

One thing is clear these days: restoration is becoming increasingly hard to do. We not only have to achieve multiple benefits with each project; get more bang for every buck; navigate politics, permitting and outdated ways of thinking; listen more carefully to community concerns and be more inclusive in decision-making; we also have to do it all faster because of climate change.

One question emerges again and again in every restoration conversation and project update: did we improve conditions for fish and wildlife, or enhance ecosystems processes?

The importance of monitoring the results of our actions and investments, and of having strong, shared metrics to do that with, cannot be underestimated. Good monitoring also requires a strong dose of humility. We will not achieve perfection, but can we find a way to be comfortable with adequate improvements? Keeping in mind the bigger picture are things better or worse? In a system so altered by our activities and so filled with invasives, contaminants and other stressors, it is tough to tease out cause and effect, let alone progress. But we must try. There are signs now that we are doing a better job of this.

The wetlands regional monitoring program, finally off the ground twenty years after it was first conceived, seems to be promising some answers.

Science, data synthesis, and a long term commitment to monitoring will take us far, but in recent years, as inequities pop our Bay Area bubble and climate extremes challenge us to the core, we are reminded again of how important people are in our restoration work. We are reminded that not everyone has the time and money to get involved in restoring our nest. We are reminded that there is suffering and injustice that access to wildness, and opportunities to do hands-on restoration or training for environmental jobs, can ameliorate.

In closing, I just want to acknowledge that this issue, despite the abundance of stories and voices, only touches the tip of the restoration iceberg. While we couldn’t cover every story now, we have likely covered most in the past.

In other news, this special almanac of restoration will be our final issue of Estuary News. After 30 years of building a community around Estuary stories and storytelling, it is time for us to leave the scene and make way for something new. We had a good run, and we thank you for your loyal readership. This June you’ll hear from us about how to access our rich library of stories in the future. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile, keep telling those stories! Keep making it right! We’ll be listening.

— Estuary News Team

Audio Editor: Amy Mayer

Quote Review & Video Production: Kim Hickok

Production Support: Roland Greedy & Chris Austin

Music: Peter Rubissow