Now in its 17th year of monitoring and treatment, the San Francisco Estuary Invasive Spartina Project remains a uniquely ambitious invasive plant removal effort: from its timeline (indefinite) and size (covering 70,000 acres with more than 150 landowners and managers) to its budget (about $50 million to date) and use of technology (genetic testing, GIS, airboats, helicopters). It’s been an effective one, too, reducing stands of invasive cordgrass in the region to a tiny fraction of what they once were.

“We are excited at the continual progress over two decades, even with all the permitting and pandemic challenges,” says project manager Marilyn Latta of the California State Coastal Conservancy, which manages the Invasive Spartina Project (ISP) in partnership with the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The ultimate goal of all this work is to replace invasive cordgrass species with the native one—a distinction that untrained eyes are sometimes unable to make, though the invasives play a very different role in local ecosystems. Found everywhere from upland areas to oft-inundated mudflats, patches of invasive cordgrass can often be accessed only at certain times of day, when the tides are right. And even then, crews require specialized equipment to access eradication sites.

There are four different invasive cordgrasses in the San Francisco Estuary—all of which are treated by the ISPbut by far the most problematic is a hybrid between native Pacific cordgrass (Spartina foliosa) and non-native smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), which was introduced from the East Coast in the 1970s as part of early Bay restoration efforts. The hybrid grows taller, more densely, more aggressively, and in a wider range of conditions (from mostly submerged mudflat to mostly dry marsh and upland transition zones) than all other versions of the invader. Where it grows, it destroys habitat that native plants and animals depend on.

Since 2005, the ISP has been methodically using high-tech tools to identify stands of intruders and hybrids, and eradicate them with carefully targeted herbicide treatment. It is a continual battle pitting a broad network of staff and stakeholders of the project against the plants’ rapid spread.

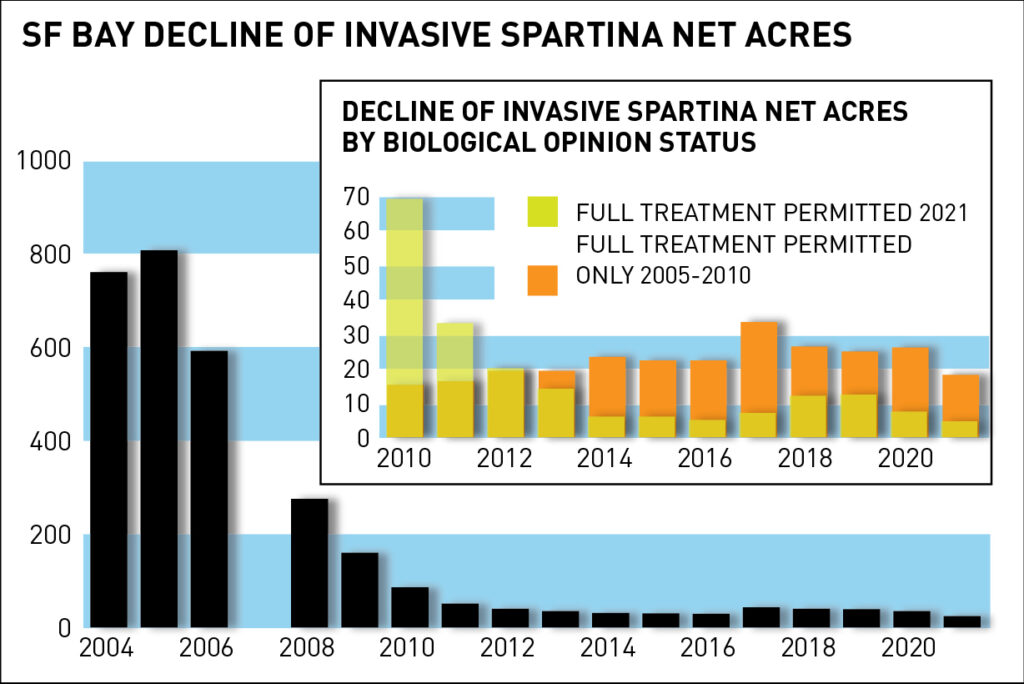

This year, 20.5 net acres of invasive cordgrass have been detected within the San Francisco Bay’s marshlands, down from more than 800 net acres at the treatment outset in 2005. The bulk of those remaining acres are in areas that were closed to invasive cordgrass removal in 2011 due to federal concerns over the endangered California Ridgway’s rail.

However, the initial closure to protect the rail was much more extensive. The last five years have been spent gradually phasing in cordgrass treatment across roughly half of the marshland that had been included in the initial closure area—while monitoring rail numbers. The results from those areas have been positive: rail counts have held steady, while invasive cordgrass has dropped dramatically and rapidly. “In just a few years, we’ve seen a more than 80% reduction in invasive Spartina at many of those phased sites,” says Latta.

The project is consulting with USFWS for a new permit in May and Latta is hopeful that additional areas will also have their treatment restrictions lifted, allowing a phased approach including treatment, revegetation, and rail protections and monitoring. “We’re at a critical point, because the invasive [cordgrass] continues to pump out seed to all the areas we’ve already treated,” she says. “If we can’t complete this effort, all of the other restoration is at risk.”

Once the initial restricted areas were opened up, progress was rapid, benefiting from myriad incremental advances in methodology accrued during the projects’ two decades.

Each marsh is unique in terms of access, hydrology, elevations, and other species that are present. Beyond the physical site logistics, the methodology and technology (such as GIS software and field applications) have also advanced over time.

While simple changes, like whether each day’s GIS field data uploads remotely in real time, or needs to be manually uploaded from the office, have greatly improved workflow, there have also been more sophisticated improvements.

“This project stretches the boundaries of the tools and products we use,” says Latta, adding that the project’s GIS manager Ingrid Hogle has worked with the engineers at ESRI to modify and tailor the software and the GIS tools to better fit the program’s needs.

Some tools, such as ISP’s custom code to run data analyses in the field, using genetically-verified reference information to provide an identification, did not exist at all at the outset of the ISP.

Another improvement uses specialized small-gauge, low-pressure “Intelli-spray” reeled hoses, allowing for more efficient, targeted herbicide application at a greater distance from the staging area.

By 2019, 14 years into treatment, the ambitious initiative had branched out into many new frontiers, thanks in large part to a grant awarded by the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority and administered by the California Invasive Plant Council (Cal IPC), an Invasive Spartina Project partner. Among other things, that funding supported a two-year project in which the Invasive Spartina Project served as a nexus for Conservation Corps workforce trainings, led by Cal-IPC and other ISP partners such as East Bay Regional Parks and Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District.

The trainings provided crews with contextual information about habitat restoration and invasive plant treatment, says Claire Meyler, the training coordinator with Cal IPC. “We would talk about Spartina really as a springboard to talk about bigger picture ecological ideas—like the importance of protecting the Bay and the danger of invasive plants,” says Meyler.

“These trainings have been huge,” Latta adds. “It’s great to get younger and [more] diverse and underserved community folks out in the field to receive job training on Bay ecology and wetlands.”

This training can serve to transition the participants from manual labor to informed, empowered crews.

“The crew leaders felt a lot more confidence,” says Cal-IPCC’s Claire Meyler, who led the trainings. “A lot of the times they can feel like they’re hired hands, doing work where they maybe don’t understand the whole frame of reference as to why we do this. This gave them more [tools] think in those bigger terms about what it takes to actually make a plan to manage invasive plants in a landscape.”

And since trainings were conducted by professionals working in the field, they offered direct access to potential mentors and other connections for trainees who might be interested in pursuing a career in the field.

“It’s not easy to get into any career, and this career is not the most well known,” says Doug Johnson, director of Cal IPC. “By integrating with [professional partners], the crew members were learning directly about land management locally, from people who are working in it professionally.”

Despite all the new avenues of implementation for the Invasive Spartina Project, the leaders and crews have never lost sight of the need to ensure they are actually benefiting the species and habitat they set out to save.

An important monitoring effort to evaluate this impact was also funded by the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority grant. Point Blue Conservation Science was enlisted to update to the bay’s California Ridgway’s rail population estimate, which found that the bays rail count has increased by roughly 200 birds since 2009-2011, the last time a baywide estimate was conducted. These counts are particularly critical to the ISP as concerns over rail populations are what led to some treatment areas being closed to the project in 2011.

Abundance of these rails is estimated via a formal method of call counts at select sites, during breeding season. The new report, which was released in January 2023, covers 2019 through 2021. In the new survey, methods were revised to be more closely aligned with the North American Secretive Marsh Bird Monitoring Protocol, says Latta.

“These survey results and the substantial revegetation of native Spartina and other native species make me hopeful that we’ll be able to get approval to continue treating the remaining areas,” says Latta.

Looking ahead, Latta says that she sees a steady march to an actual finish line. If phased treatment is approved at remaining sites in 2023, she is optimistic that detectable invasive cordgrass might be eliminated within the next decade. After that, the hope is to transition to long-term monitoring by individual landowners.

Top Photo: Treatment near Bair Island with airboat. Photo: Drew Kerr, ISP