As a source of flowing water, upper Coyote Creek is unreliable at best. Though storms swell its banks in winter, Mediterranean-climate summers shrink this South Bay stream to a series of isolated pools by August.

“By October right before the rains come, we’re down to these really small pools that have all the fish in them,” says retired U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ecologist Rob Leidy.

Leidy and UC Berkeley fish ecologist Stephanie Carlson began monitoring the annual dry-down of upper Coyote Creek in 2014, with the help of Hana Moidu and other graduate students. The creek itself originates in Henry W. Coe State Park and flows to the Bay through Coyote and Anderson lakes south of San Jose.

The scientists have found that while the intermittent reach of creek above Coyote Lake appears to be a death trap for aquatic organisms, it is actually dominated by native fishes and other wildlife. This makes Coyote Creek a rarity among California’s highly invaded, diverted, and degraded waterways. In dry times, the pools are a West Coast version of the Serengeti’s famous watering holes: they teem with wildlife ranging from lizards and snakes to mountain lions and deer.

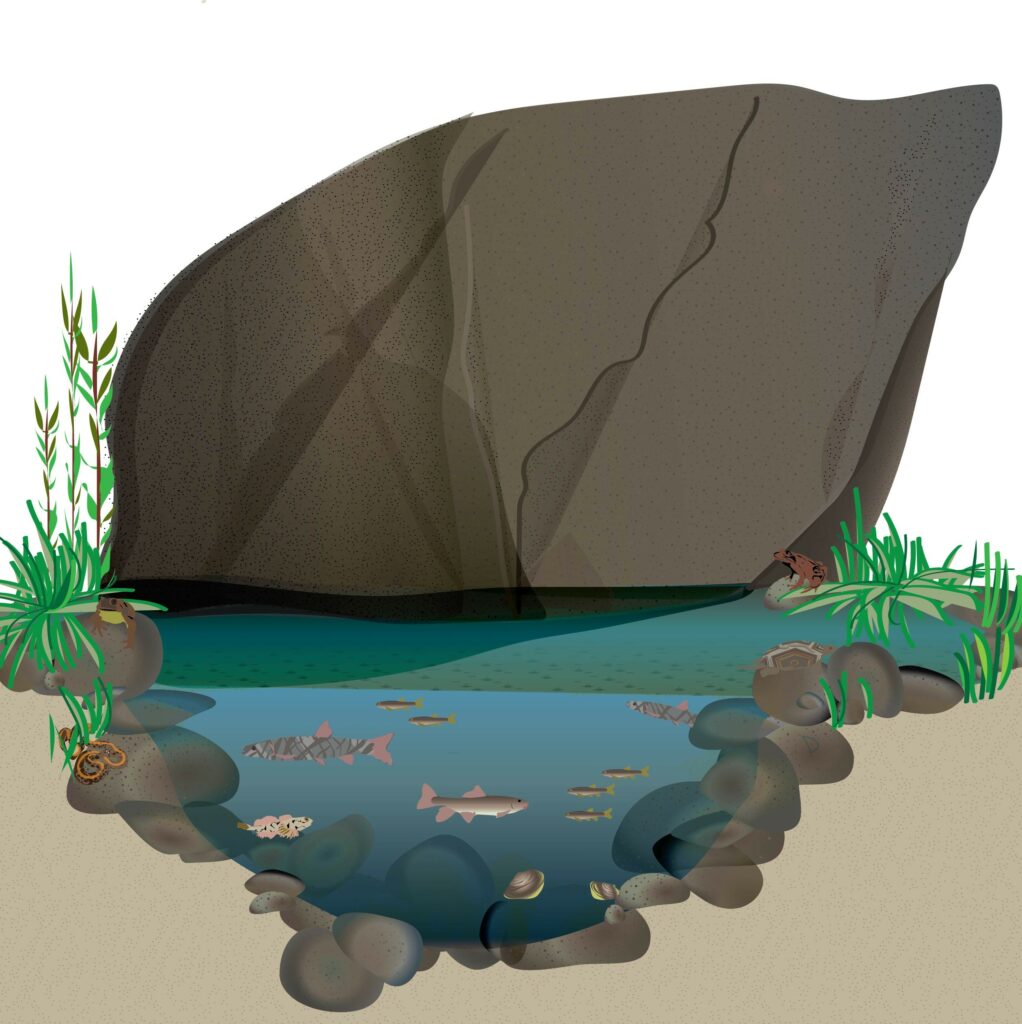

Across six years of surveys, the scientists have also noticed another peculiar detail: the pools that persist are always in the same locations. Given the importance of the pools for wildlife, the researchers wondered why some endure while others tend to evaporate. The most reliable, they found, had several features in common. Many were adjacent to massive, sometimes house-size boulders. Landslides had tumbled the boulders into the river from the steep banks.

“The thought is that the high-water flows of winter will scour deep along the boulder and form deep pockets for water,” says Moidu. “Often at the end of the summer season, this is the only surface water that remains.” The boulders also offer shade, slowing evaporation.

The most persistent pools also possess a secret source of water: an underground spring. The five-kilometer study reach begins just downstream of Gilroy Hot Springs, which flows even through the driest summers. Yet this hidden water supply only became clear after the extraordinary rains of 2017. “It was only in that really wet year that we saw surface connections to several springs along our study reach,” Carlson says. “It made us realize that perhaps in drier years, there was a subsurface spring connection that might have been contributing to the persistence of those pools.”

The springs arise from the fact that Coyote Creek lies in earthquake country. A fault runs along the creek’s length. Cracks in the bedrock underlying the creek bed allow groundwater to fill the pools.

“These pools are disconnected from the annual rainfall because the water that comes into many of the pools is from deep aquifers,” Leidy says. “This decouples them in the short term from the effects of drought.”

Conditions within pools depend heavily on their size. The largest, deepest pools are cooler and have more dissolved oxygen, enabling them to host larger adult fishes, as well as species such as the endangered red-legged frog. By contrast, temperatures in shallower pools can go from the 50s at night to the 80s on hot afternoons, pushing animals to their thermal limits. The most common vertebrates in these puddles tend to be small organisms such as juvenile southern coastal California roach.

The team has even found one native fish that doesn’t require open water to survive. The Pacific brook lamprey can wriggle its wormlike body into the few centimeters of water around the cobbles and gravel lining an otherwise dry pool. Within this hyporheic zone, the lamprey can lay low for weeks until rain returns.

“It seems many native species have adaptations that allow them to tolerate these very harsh conditions,” Carlson says. The more natural flows in intermittent streams, the researchers suspect, keeps non-native fish species at bay. Yet these intermittent waterways, she says, “are very underappreciated in terms of their importance for supporting regional biodiversity.”

In California, intermittent streams make up more than half of the state’s river miles. Along those, Leidy has found summer pools in waterways such as Alameda Creek, as well as streams in the Diablo Range, northern intercoastal range, and Central Valley foothills. But he suspects there are far more.

“It might be a really good strategy to go out and identify areas where these persistent pools are located,” he says. “Then you can target those areas as refuges to climate change in the future.”

Top Photo: Scientist Mike Bogan sampling a deep pool. Photo: Rob Leidy.

Previous Estuary News Stories

Other Links

Biodiversity Value of Remnant Pools in Intermittent Streams, Aquatic Conservation, 2019

Prey and Foraging Behavior of the Whiptail Lizard, North American Naturalist