In the mountains and foothills of California, an enduring drought has depleted the state’s major reserves of water. There is virtually no snowpack, and most of the state’s large reservoirs are less than 40 percent full. But in the central Sierra Nevada, a trio of artificial lakes remain flush with cold mountain water. The largest of them, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, from which millions of Bay Area residents receive water, is more than 80 percent full.

This remarkable plentitude is the outcome of careful planning by the agency that manages the Yosemite National Park reservoir plus conservation by Bay Area residents, who use less water per capita than most other people in the state—between 35 and 65 gallons per person per day. The statewide average is 82 gallons.

But some environmental advocates are hardly cheering San Francisco’s water conservation success. Instead, they’re accusing the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission of hoarding its water through an excessively conservative management plan they say harms the environment and benefits almost no one—not even the city dwellers who use the water.

“People in San Francisco conserve water during droughts, thinking they’re helping the environment, but they aren’t because the water’s just staying in the reservoir,” says Peter Drekmeier, policy director of the Tuolumne River Trust.

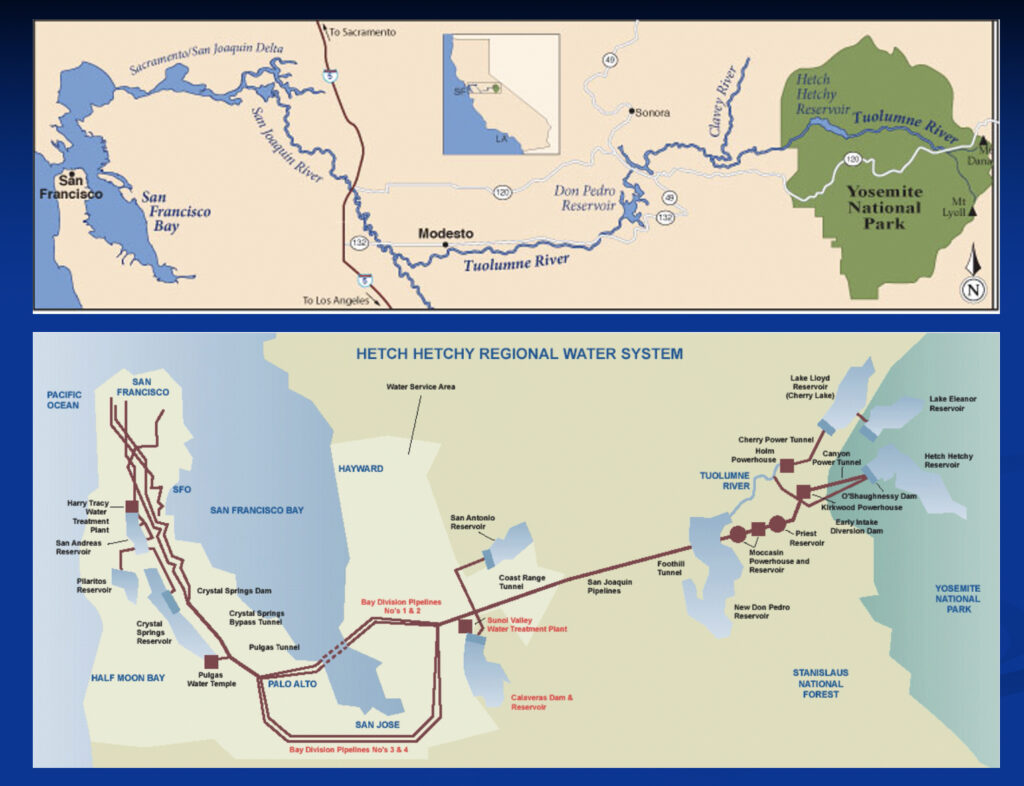

At a public hearing hosted by the SFPUC on August 23, Drekmeier presented a statistical analysis of the commission’s water management plan. He argued that the agency, which manages Hetch Hetchy and a network of other reservoirs with two local irrigation districts, could release more water into the Tuolumne River, a San Joaquin tributary, without affecting customers or significantly compromising its supply. Increased flows would provide benefits for the San Joaquin watershed’s struggling Chinook salmon population, as well as Delta communities now facing water quality issues associated with low river flows, warm water, and resulting toxic algae blooms.

In 2018 state water officials adopted, but did not implement, a plan to keep 40 percent of the basin’s total runoff, or unimpaired flow, in the river in the spring months. The Tuolumne’s flow usually runs about 20 percent of unimpaired, and through the 2012-16 drought it averaged a scant 13 percent.

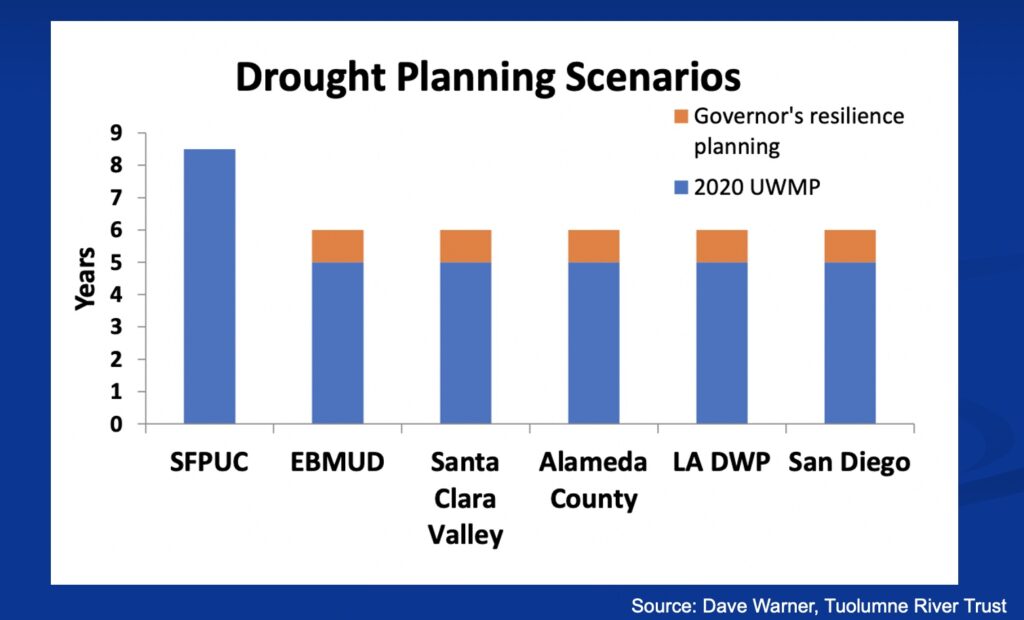

The SFPUC and the Turlock and Modesto irrigation districts, though, have not budged from their water management strategy, claiming there is essentially no water to spare. The commission’s plan is designed to protect San Franciscans from a hypothetical worst-case scenario of 8.5 years without significant precipitation. This imagined dry spell—a stress-test that planning documents refer to as the “design drought”—combines two historic hydrological periods, the droughts of 1976-77, which was the driest two-year period in state history, and 1987-92, which was one of the longest. The odds of such a long, dry drought occurring are exceedingly small, but the idea is to be safe.

“The consequences of being wrong and running out of water for water supply and the environment are enormous,” the PUC’s assistant general manager of water operations Steven Ritchie said at the commission’s August 13 hearing.

The SFPUC’s water management strategy is simple: In a dry year, it assumes that a devastating drought has begun. In a wet year, it assumes the drought will begin the following year. With each wet winter, the starting point resets.

“It doesn’t pay off at any time to assume that the next year or two will be wet,” Ritchie told the commissioners. “We have to assume they will be dry, and if they’re wet, we have a beneficial addition to storage.”

By this approach, the PUC’s water supply system—which also includes Lake Eleanor and Cherry Lake—is maintained at high capacity. On the day the commission held its meeting, each of its three reservoirs was roughly nine-tenths full.

The plan is overkill, Drekmeier says. Using data from the PUC’s “Long Term Vulnerability Assessment,” he calculated that the design drought has one chance in 70,000 of beginning in any given year. He wants the commission to shave one year from its design drought, and he requested that the commission formally consider this as an “action item” at a future meeting. Making the design drought a 7.5-year event, he says, would allow the PUC to release enough additional water from their reservoirs to meet the 40-percent unimpaired flow provision of the Bay Delta Water Quality Control Plan while causing no impact to San Franciscans.

“They’d still have the water they need, and the Bay-Delta ecosystem would have the water it so desperately needs,” Drekmeier says.

At last week’s hearing, several members of the public called in with comments on the design drought dilemma. One man told the commission its water management plan is unreasonably conservative.

“The risk of running out of salmon is far, far greater than the risk of running out of water,” he said.

Strained by a variety of factors, including water diversions, the Central Valley’s once-plentiful Chinook have crashed in the past 70 years, according to records from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. In the 1950s, the Tuolumne River alone saw an average return of about 25,000 adult fall-run Chinook. Spawning runs plunged the following decade, as new Delta water pumps increased deliveries to farms and cities. The salmon decline continued through the 1970s, when less than 2,000 fish spawned most years. The 1980s saw a slight resurgence, but in the past 15 years, fewer than 1,000 fall-run Chinook have swum upriver most seasons. In 2021, scientists counted just 186 of the fish in the Tuolumne.

Water distribution agencies tend to deny responsibility for ecosystem degradation in the rivers they divert from, often attributing fish declines to factors other than water depletion—things like habitat loss, invasive species, climate change, pollution, and overfishing. The San Francisco PUC and its partner irrigation districts have offered to implement a variety of measures to help salmon, including restoring small patches of floodplain, restoring spawning grounds with gravel dumps, controlling nonnative predatory bass, and releasing so-called “pulse flows,” brief bursts of high currents intended to carry juvenile salmon rapidly toward saltwater, increasing their chances at survival. (The agencies proposed recapturing those pulses near the confluence with the San Joaquin.)

As for sacrificing more water, the agencies have declined. The PUC has argued that San Franciscans are precariously vulnerable to water shortages and that a bad drought coupled with flow requirements for the lower Tuolumne River would mean severe water rationing. For this reason, the City and County of San Francisco sued the state early last year to block its water quality plan, arguing in legal documents that increasing river flows could risk the “total loss of San Francisco’s water supplies during periods of drought,” causing “unfathomable social, economic, and environmental impacts in the Bay Area” and requiring water rationing as high as 95 percent.

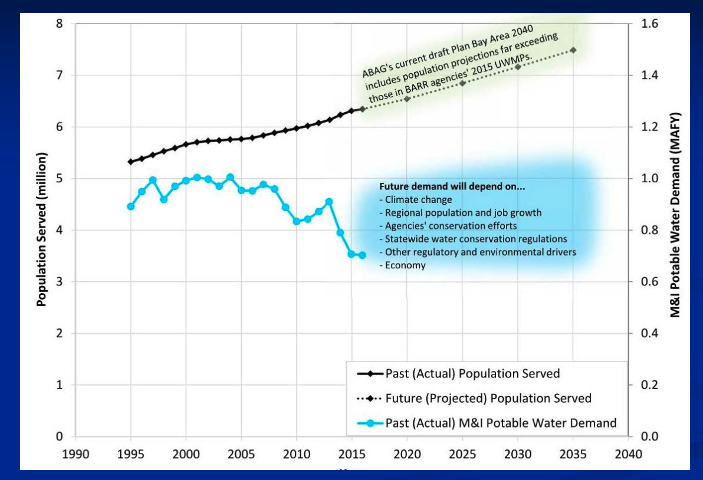

But city water managers have exaggerated how much water their customers use. Collectively, these 2.7 million people consumed 195 million gallons per day in fiscal year 2020-21, according to the PUC water division’s latest annual report. Water use has sharply dropped since last century and has been under 200 million gallons per day for nearly the past decade. But in their court filing last year, the city said “present-day demand” was 238 million gallons per day. Also that January, in a letter to a group of Bay Area water suppliers, PUC staff presented drought rationing warnings that Drekmeier, who ran reverse calculations to check the numbers, says were based on a regional daily system demand of 265 million gallons per day—30 percent more than actual use.

The SFPUC also predicts that their retail and wholesale customers will need more water in the future—which experts say is unlikely. Even with more people and a larger, busier economy in the future, urban Californians will probably be using significantly less total water in a few decades than they are today, according to the Pacific Institute’s Heather Cooley, who analyzes water use trends for the Oakland-based think tank. Since the 1970s and 1980s, she says, communities across the western United States have improved efficiency in home appliances and landscape irrigation systems. Greywater and water recycling programs have become standard, especially in new developments. These measures have offset the water supply strains of population growth, leading to reduced total water use.

“I think we will continue to see this trend,” she says.

While the SFPUC may have plenty of water, it does not have a backup supply—which, Ritchie explained at the hearing, is one of the reasons for his precautionary approach.

“No one will step in to help San Francisco in an extreme drought,” he said.

The SFPUC’s system is not connected to the major state and federal water systems. It has minimal access to groundwater. The agency has also not invested heavily in desalination or water recycling, as some water suppliers elsewhere in the state are doing. The rain and snow that falls in the Sierra Nevada is its lifeblood.

This isn’t the case for other Bay Area water providers. In the South Bay, Valley Water serves 1.9 million people. While the agency receives a little over half its water from other major providers—including the SFPUC—it also uses local groundwater and runoff from local watersheds. This makes management a less harrowing affair.

“We don’t aim for a specific volume in storage since we have a diversity of supply sources and delivery methods, included treated surface water, untreated surface water, groundwater, and recycled water,” said Matt Keller, Valley Water’s public relations supervisor.

In much of the state, water conservation is a way of life—and especially so in times of drought. The problem that Drekmeier and others have frequently pointed out is that, in the SFPUC’s service area, this doesn’t necessarily do any good for the environment. During the five-year drought ending in 2016, lawns were browned and toilets yellowed. The water saved through these efforts, though, was primarily used to buff up reservoir storage, leaving the Tuolumne River running at a trickle. When the drought ended in 2017 with an extremely wet year, the PUC had no choice but to open the floodgates on its dams. Torrents of water flushed downstream, but with little ecological value.

“All that water that people conserved didn’t do any good for the ecosystem,” Drekmeier says. “It just got dumped.”

Top photo: Tuolumne during low flow conditions. Photo: National Forest Service

Bay Area Regional Reliability Drought Contingency Plan

California Urban Water Use Map

Water is life. It’s also a battle. So what does the future hold for California? – CalMatters