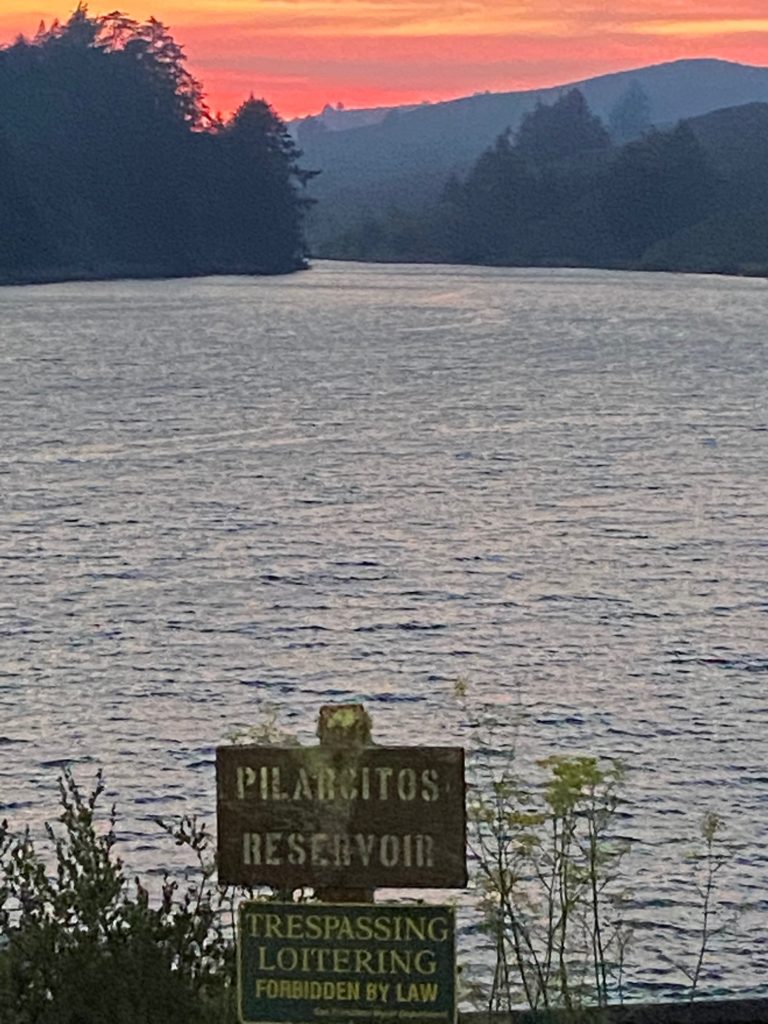

When the August 16 lightning strikes started forking from the sky to the ground in the Bay Area, Sarah Lenz was driving back from the scene of a vehicle accident and fire. It was pitch dark in the 23,000-acre Crystal Springs watershed in San Mateo County where she is a watershed keeper and supervisor, or what you might think of as a water ranger—something like a park ranger but who protecting source watersheds for drinking water not parks.

Lenz’s main responsibility is to be fully present in the watershed when something happens—a first responder to crashes, fires, slides, floods, suicides, and trespassers. Crews coming in from the outside would just take too long to get to such events—opening locked gates, getting lost on branching fire roads, not knowing the lay of the land. “It’s always fun at night when I turn on the lights of the patrol vehicle, you might see a fox,” says Lenz, who just turned 50.

Lenz grew up in the Midwest, where thunderstorms are nothing special, so the flashes of light on the horizon on her drive back to the 100-year-old keeper cottage she now inhabits as part of her job didn’t worry her. But when she got home she only took her boots off. “It started storming, not just flashes but really intense wind gusts and lightning strikes. Just as I was tying my shoelaces again so I could drive to higher ground, Cal-Fire called me to get out of there,” she recalls.

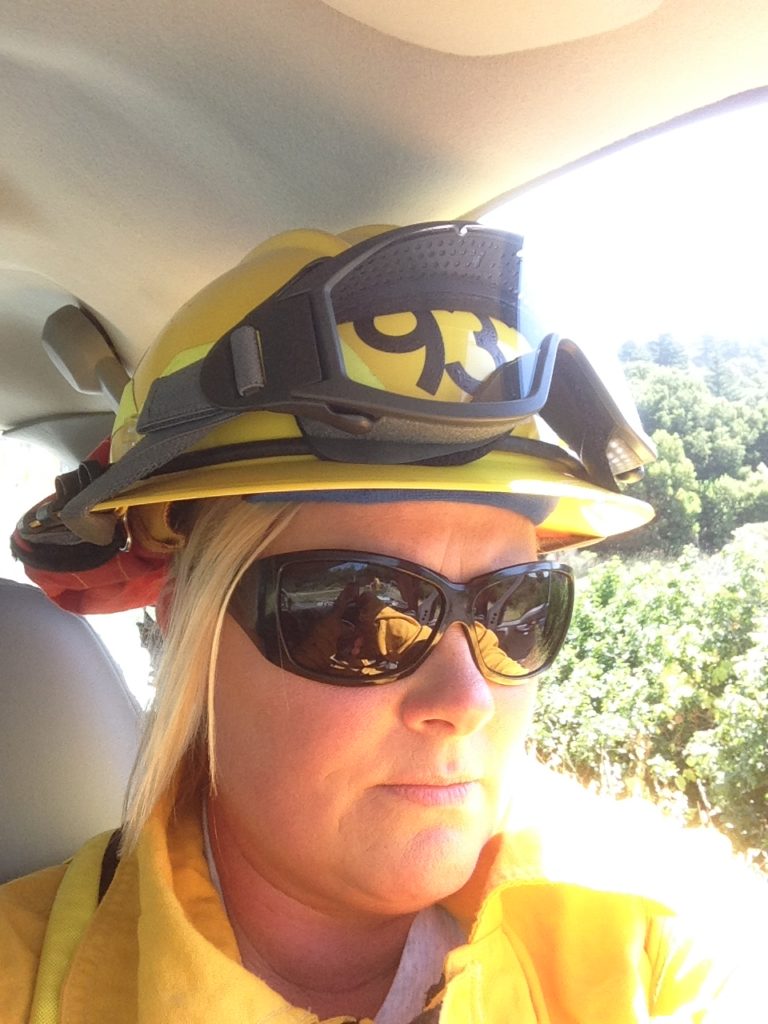

It was 2:00 a.m. Lenz checked the lightning strike map on her phone. “I could see in real time where they were hitting,” she says. She also checked wind speeds and humidity at the Spring Valley weather station. Then she donned her fire retardant Nomax suit and climbed in her patrol truck, which carries a fire pumper and 110 gallons of water. She chose a road to a high spot where she could see what was going on in the watershed.

A few minutes later Lenz changed direction to respond to a radio call about a fire on the golf course. “As I came up from the valley around the crest of the hill there was a wall of fire. I was surprised I didn’t know there was fire sooner, but the mountain just hid it, flames up at the tops of two pine trees. I checked to see if the scene was safe. I drove around the trees to see if the fire was on both sides, but it was only on one. I let dispatch know I was on Sawyer Ridge. Then fired up my pumper, knocked down the flames in the crown of the trees, and kept the fire contained to one side of road,” says Lenz.

Fire response is one thing that hasn’t changed about the job since the first watershed keepers were hired by Spring Valley Water Company in the late 1800s. Early keepers spent a lot of their time shooting “varmints,” ejecting poachers, and stocking lakes with the favorite fish of the water company’s directors, who used the Crystal Springs area for private recreation. The City of San Francisco acquired the company in 1930, as well as more than 38,000 acres of East Bay watersheds. Since then, keepers have been tasked with everything from checking dams and opening valves to guiding firefighters, police, and more recently Bay Area Ridge Trail hikers into the remote backcountry.

Aiming her hose at the two pine trees this past August, Lenz soon ran out of water and radioed the dispatchers she was heading out for more. “We are responsible for any initial attack on the fires, we know the layout, the roads, where the water sources and fire hose bibs are. We have all this stuff set up strategically for fire-fighting,” she says.

As the night waned, her co-keepers came on duty and began to pitch in, finding four other fires. Two “street engines” from a nearby city responded to the Sawyer Ridge fire, Lenz recalls. Though the trucks were not equipped to navigate dirt roads, Lenz managed to get them to the scene. “We keep our roads in good shape,” she said. Later she brought a Cal-Fire crew to the golf course fire, where they all cut a line with hand tools.

“We had eight lightning strikes in our Peninsula watershed that night, but thanks to Sarah and other keepers and responding fire agencies none of them merged into a big fire like the SCU complex in our East Bay watershed,” says SFPUC’s Natural Resources Director Tim Ramirez. “Our watershed keepers don’t need to run the drinking water system anymore, but they do need to live on the property and patrol it—eyes and boots on the ground.”

In his last 15 years overseeing the watersheds, Ramirez has expanded keeper roles to embrace more typical park ranger roles, such as working with trail docents and sharing natural history with visitors. But it’s their finely-tuned sense of the local landscape and conditions that remains most valuable of all.

“Watching the ridge of the coast range, sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between smoke and fog around here,” says Lenz.

After the August fires burned through so much of California, her department made some changes. “Two weeks later there was another lightning event forecast, and this time we were more pro-active. We staffed people through the night; we put float tanks out in the lake to supply water to water tender trucks; we tested all our fire hose systems; I kept my fire gloves on the dash and my Nomax right behind me in the seat. It’s a little intense living right in the middle of the forest in fire season.”

Lenz put away her Nomax after the November rains. When winter storms hit the watershed, she’ll be on the lookout for flash floods and downed trees: eyes and ears on the ground year-round.

Top photo: Lightning strike this August on the Peninsula watershed. All photos: SFPUC

Read about the SFPUC’s first female watershed keeper, Gayle Ciardi, and review other keeper comments.