Ted Frink recalls watching Jacques Cousteau’s television specials when he was growing up in coastal Orange County. “I envisioned myself as Cousteau,” says Frink, a fisheries biologist with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) now approaching retirement. “My folks encouraged my interest in science. I knew I could be a biologist.” That early inspiration sparked a long and varied career, culminating in his work as chief of DWR’s Special Restoration Initiatives Branch and his role in mitigating obstacles to salmon and steelhead passage in streams all over the state.

Frink focused on salmonids and other anadromous fish early on, graduating from Humboldt State in 1984 with a degree in fisheries ecology and a minor in hydrology. His first professional assignment was in Imperial County with what was then the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG), testing ways to control the exotic waterweed Hydrilla in local canals. “This convinced me I could find a job,” he remembers. Then came salmon stream restoration work with the US Forest Service in the Klamath region, collaborating with the Yurok and Hupa tribes. One restoration gig took him to Red Cap Creek, locale of some much-debated 1967 sasquatch footage (the so-called Patterson-Gilman film). Frink didn’t encounter any large hairy primates, although there were “funny smells and strange noises in the night.”

With federal career pathways less than promising, Frink hired on with the East Coast-based consulting firm Ebasco Environmental. That took him to Superfund sites from Hershey, Pennsylvania, where the discharge ponds smelled like chocolate, to a Denver, Colorado locale full of “chemicals no one in their right mind would put together.” He also conducted fisheries and hydrologic studies in support of the Mono Lake Committee’s suit against the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which led to a landmark court decision requiring restoration of historic lake levels and tributary stream flows. “This is where the Public Trust Doctrine became a mantra in my career as an ecologist,” says Frink.

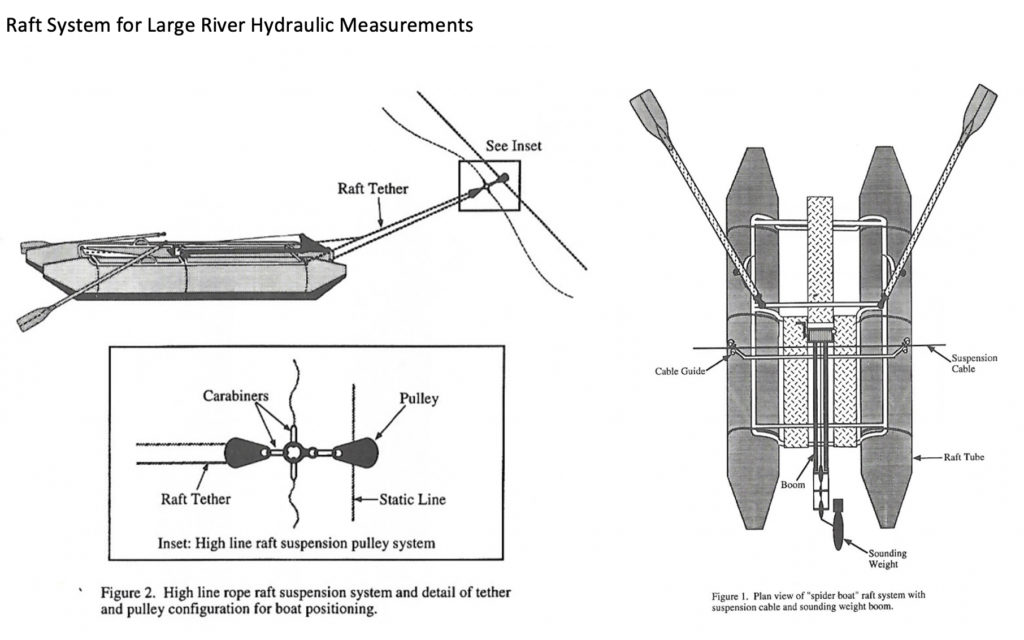

One consulting project proved more adventurous than he had bargained for. In the late 1980s, San Joaquin Valley irrigation districts were planning hydropower dams in the Tuolumne River watershed west of Yosemite National Park, although the river was a candidate for wild and scenic status. During that project Frink originated a technique, still in use, for measuring flows in high-velocity streams using climbing gear to hold the surveyors’ boat in position (see diagram). To get to remote creeks, Frink and his crew flew in a Huey 500. Piloting the Huey, the fastest helicopter available at the time, were Vietnam veterans who had survived being shot down in combat. The pilots had to avoid wire cables that had been strung across the Tuolumne canyon in the mining era, made more visible by colored flags and hanging cable cars. On one trip down-canyon, doing a hundred miles an hour, the copter began to shake violently. Landing safely on a sandbar, the pilot found that one of the main rotor blades had “a giant kink in the middle” from impact with an unseen cable. Frink and his co-workers had to hike five miles to get out of the canyon. Investigators later found that the warning flags and cable car had been moved off to the sides. The responsible parties were never identified, and the dams were never built.

Friends suggested that Frink look for a state job as a fisheries biologist; he applied with both DWR and DFG, and was hired by DWR in 1991. “I didn’t know what to expect,” he says. “I knew [how to] work in fisheries but now I had to understand engineers to get things done.” He spent five years in the Division of Environmental Services, initially working on protecting fish from entrainment at water diversions but then on fish passage improvement.

Legislation introduced by State Senator Byron Sher had funded DWR to investigate potential new storage reservoir locations while also identifying inoperable, outdated, or dangerous dams that should be removed, or could improve fish passage to and from habitat up and downstream. “We realized it would be a non-starter if we had to call it the Dam Removal Program — too controversial — so it became the Fish Passage Improvement Program,” Frink says. A five-year study generated a roster of potential sites.

It’s been a long haul, but some dams have come down, or are on their way out like a dam on York Creek in Napa County: “We’re getting close to making that project happen, a dam removal that we initiated for a little creek with a steelhead run that flows through St. Helena. Another I’m proud of was the San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River, where the Coastal Conservancy took the lead — a big milestone for me and a great example of collaborative work.”

He hopes to see dam removals on the Klamath River in the not-too-distant future as well. Frink also worked on the Fremont Weir in the Yolo Bypass, a bottleneck where migrating salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon were repeatedly stranded. “We finally got a design in the works to build a bigger and better fish passage notch in that flood system weir,” he says.

Frink has had a hand in a long list of projects and initiatives: partnering with the Winnemem Wintu Tribe and NOAA Fisheries to study options for fish passage over Shasta Dam; helping develop an acoustic sound barrier to guide migrating salmonids at Georgiana Slough on the Sacramento River; restoring tidal wetlands at Dutch Slough; and administering the Urban Streams Restoration Grant Program. Frink recently took on a project at the Salton Sea, creating 4,000 acres of saline pond habitat at the mouth of the New River for fish (including desert pupfish) and migratory waterbirds. The project will replace habitat lost due to Colorado River water transfers and address air quality problems from seabed dust.

Inevitably there have been frustrations. Searsville Dam, owned by Stanford University, has been in limbo for 15 years. But overall, Frink says his years of experience working collaboratively with multiple entities have paid off, whether it’s water districts, tribes, landowners, farmers, or the owners and operators of water facilities. “The biology is straightforward,” he says. “The engineering is unique but straightforward. It’s always working with others that creates the challenge. It’s frustrating at times but rewarding when we actually improve a passage problem.”

After retirement, Frink will have more time for the foot and bicycle races he takes on to raise funds for Breathe California and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and for the sustainable community he’s helping develop in Costa Rica. “I expect I’ll stay involved with fish passage,” he adds. “I have a desire to keep moving it forward.”

Rebooting the Klamath, Four Dams Down?, March 2020

Calaveras Dam Tweaks Yield Results, March 2020

All photos courtesy Ted Frink.