As Bay Area cities and counties grapple with the formidable challenge of preparing for a higher San Francisco Bay, there is perhaps no better example of the obstacles and opportunities than the effort underway to adapt Highway 37.

The 21-mile North Bay corridor running from Vallejo to Novato has long been a source of tranquility and frustration. The highway offers sweeping views of tidal baylands dotted with roosting waterfowl and shorebirds plumbing mudflats for food, along with mile upon mile of open space – a bounty of natural land made possible by decades of careful planning and restoration work. And commuters often have ample time to enjoy the scenery: Highway 37 is one of the most congested in the region, with peak traffic producing delays as much as 40 to 80 minutes in each direction.

Congestion isn’t the only problem facing Highway 37. This past winter a combination of storms and high tides caused Novato Creek to spill onto the low-lying highway, shutting it down for a total of 28 days.

“The only upside of the storm event is that it highlighted how vulnerable portions of this corridor are,” notes Suzanne Smith, Executive Director of the Sonoma County Transportation Authority. “If a portion of the corridor goes down it has a significant impact on alternative routes which are limited in the North Bay.”

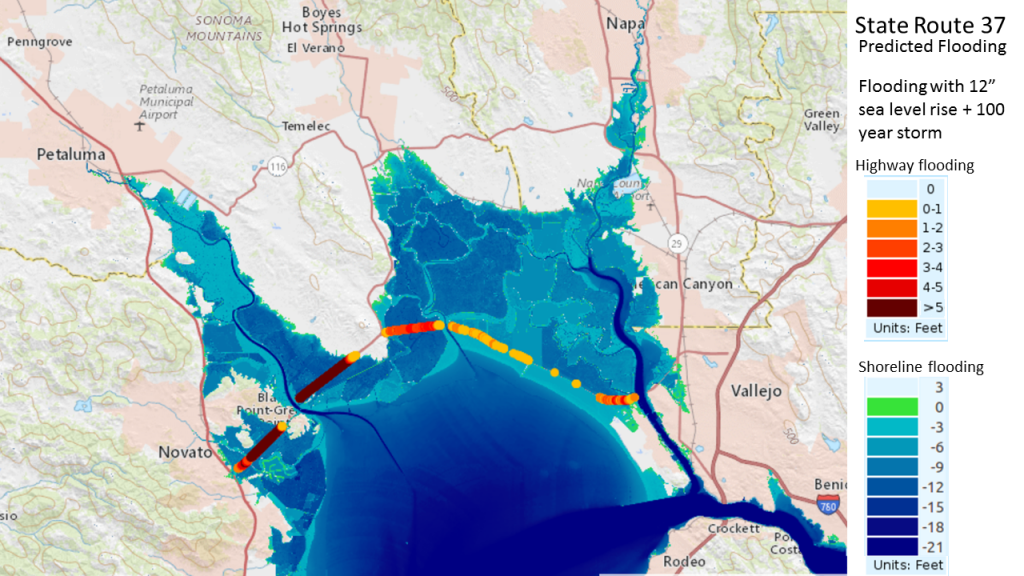

While it wasn’t the first time flooding impacted Highway 37, it’s very clear that it won’t be the last. A 2016 study by the Road Ecology Center at the University of California, Davis pointed out the highway’s numerous vulnerabilities to flooding and sea level rise, and estimated that within 30-40 years various low levees protecting the highway could fail to hold off rising bay waters.

“Obviously there was a growing sense of urgency due to the traffic, but the floods from last winter and road closure in Marin drove home the point that the sea level rise that seemed far off maybe isn’t as far off as we think,” says Daryl Halls, Executive Director of the Solano County Transportation Authority.

Both Smith and Halls staff the Highway 37 Policy Committee, a group composed of twelve elected officials from Solano, Napa, Sonoma and Marin Counties that has been meeting bimonthly to wrestle with how to improve the beleaguered corridor before things get worse.

Like flooding, Highway 37’s congestion is projected to significantly increase in the future. And the hotspot for both problems is the 9.3-mile stretch from Sears Point to the Napa River bridge. In this segment Highway 37 narrows to two lanes more suitable for a few tractors pulling hay than the estimated 45,000 daily trips it receives today. The road lies mere feet above the high tide line, with only a narrow strip marsh between the highway and the bay.

Intertwined with the discussion of Highway 37’s future are its surroundings. Over the past few decades, the restoration community has made a significant investment in conserving and restoring thousands of acres of wetlands and open space.

“This project is the opportunity of a lifetime because it crosses four counties, connects two major highways, and is surrounded by tremendous ecological resources,” says Jessica Davenport, a Project Manager with the California State Coastal Conservancy. “We don’t want to miss this chance to come together and create a world class adaptation, restoration, and transportation project.”

In 2015, decades of work and planning culminated with the Sears Point and Cullinan Ranch restoration projects breaching levees to cheers, as bay waters returned to several thousands of acres that had been diked off for farming over a century ago.

“We’ve been working down in the baylands since the eighties,” says Julian Meisler, Baylands Program Manager at the Sonoma Land Trust. His organization bought the Tolay Creek Ranch, the Sonoma Baylands and Sears Point – all of which surround Highway 37. According to Meisler, the Land Trust has protected about 6,500 acres just in the Sonoma County area around Highway 37. And in Solano County, Ducks Unlimited and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife have conserved and restored thousands more acres near the highway. “At least $100 million, and maybe double that, has been spent,” says Meisler.

For the restoration community, Highway 37 simultaneously presents both a tremendous barrier and an opportunity. The highway disconnects the tidally-restored baylands from adjacent open spaces, preventing habitats and species from being able to migrate to higher ground and threatening to drown them as sea levels rise in the future.

“The highway interrupts the ecological processes,” explains Meisler. “In some cases it’s preventing the marsh from moving inland, in some cases it’s preventing stormwater from flowing outward, in some cases it’s preventing tidal water from moving upstream.”

If Highway 37 were elevated, rainfall and tidal waters could flow unimpeded to and from the bay as motorists pass by high above; yielding two-way passage for both people and wildlife. “It’s probably the biggest opportunity of our generation – at least in the region – to simultaneously restore and enhance tens of thousands of acres of marshlands,” says Meisler. He argues the benefits are many: reconnecting natural processes rather than fortifying against them can help prevent flooding, saltwater intrusion, and habitat loss. “It becomes a much more functional system and probably something that is going to cost a lot less from a maintenance perspective for whomever ends up managing that road.”

Davenport agrees. She has been coordinating a group of restoration organizations and land managers that have formed their own committee, called the State Route 37 Baylands Group. “There was a concern that with this accelerated schedule for redesign and construction of the highway there might not be enough attention paid to the ecological values of the area and how to protect and enhance them,” she says. “We wanted to build on that existing knowledge and pull it together in a way that could be communicated to the transportation planners and the public.”

Looming over the hurdles facing Highway 37 is the pricetag. The 2016 UC Davis study evaluated two basic options for fixing the highway’s congestion and vulnerability to flooding: expanding the levee that the road currently sits on or replacing it with an elevated causeway. Each potential solution brings with it complex engineering problems: widening and raising the existing levee to accommodate extra lanes and future water levels raises questions about how high is high enough (a tricky issue as settlement, or compaction of the soft bay mud under the levee, already exacerbates the road’s current vulnerability to flooding). The other option, building a four-lane causeway, costs three or four times as much, but minimizes environmental impacts. This approach would reconnect ecological processes and allow for species migration and habitat transition zones.

Smith emphasizes that these options are just sketch-level concepts. “[In the future] we’ll be exploring more how you mix and match a levee and a causeway system in order to maximize benefits to the baylands and species out there,” she says. “I can’t imagine it will be just one big causeway or just one big berm, but it will be some combination.”

Indeed from a bigger picture regional resilience perspective, groups like the San Francisco Estuary Partnership would like to see every big bayfront infrastructure adaptation project like this optimized to provide multiple benefits. The Partnership’s 2016 Estuary Blueprint – the collaborative vision of 100 partners– includes a number of actions aimed at advancing projects that improve habitat, flood protection, and water quality, all in one. “With the current flood risk to the highway, and all the investments in habitat and open space around it, the solutions have to be innovative,” says the Partnership’s director Caitlin Sweeney. “This is a test of our multi-benefit mantra and mettle.”

Whatever solution is decided upon, it won’t be cheap. The estimated price tag to fix just the most vulnerable 9.3-mile segment ranges from $700 million to $2.5 billion. And to fix the whole highway? Something like $1.3-$4.3 billion.

The daunting cost is why the Highway 37 Policy Committee has engaged in serious discussion over the possibility of tolling the highway – and they are not the only ones interested. In May of 2016, a private venture group submitted an unsolicited bid to the committee, in effect offering to fully fund the project in exchange for Caltrans relinquishing the highway segment to the company, along with its potential toll revenue.

But full privatization is just one way to bankroll the project. The Highway 37 Policy Committee has been exploring other options such as a public-private partnership where risk, liability, management, and toll revenue are split between a private partner and government. This option could yield $300 million to $12.5 billion in total revenue, according to a study commissioned by the committee. The actual revenue would depend on how much the toll is (the consultant looked at a range of $2-7 dollars), how many lanes are tolled, and how the toll is assessed (via a one-time toll like a bridge, or a per mile toll structure).

While no decision has been made yet, more and more committee members have acknowledged publically that a toll seems to be the only way to raise the funds needed to fix the highway.

“The whole issue of whether to toll the corridor, that’s a huge policy call. All we’re saying is without funding you don’t have improvements,” says Halls. “That’s a question for the public – are they willing to consider what I call a ‘user fee’ to get this project going?”

Any tolling proposal for the highway raises serious questions regarding social equity. Highway 37 is the last major trans-bay route without a toll, and its commuters mostly live in the lower-income Solano County and work in wealthier Marin and Sonoma Counties.

Tolling, equity, and the ecological impacts of the proposed solutions are expected to be big topics of discussion in a series of public engagement workshops taking place in the four counties from September 20 to October 2, 2017.

As frustration with congestion increases, and water levels creep higher, there is a tension between moving full speed ahead on fixing the corridor’s issues and proceeding in a deliberate, transparent process in order to ensure all stakeholder’s concerns are met.

“We are on a timetable – just sitting and doing nothing isn’t going to work,” says Halls. “We’re trying to get all the right people to the table to not just talk but actually do something.”

As that conversation plays out, both sides acknowledge that despite the encouraging progress, the hard part is yet to come. Currently underway is an analysis evaluating both short-term options for reducing congestion in the crowded corridor, as well as long-term possibilities for the highway. Set to be complete in April 2018, the study will ideally lead into the multi-year Environmental Impact Report (EIR) process where all the stakeholder concerns will be officially evaluated. Then, if there’s agreement upon the design, permitting and construction can begin.

“How we’ll get there is unclear, and each meeting it gets a little clearer just how challenging it’s going to be,” says Meisler. “Whatever happens with Highway 37 has everything to do with what we’re able to achieve there, and the types of habitat we can restore or conserve.”

“It’s going to take time and teamwork, people working together, sharing concerns,” notes Halls. “But we’ve built up some momentum.”

Despite the long road ahead both sides remain optimistic; pointing to the vast potential that Highway 37 presents.

“The interest is there, the desire is there, now it’s just getting everybody to row in the same direction,” says Smith. “And I am optimistic that the value of the corridor is so great that we will be able to get everybody to do that.”

Note: Isaac Pearlman wrote this story as freelancer currently on leave from his position as an environmental scientist at BCDC.

UC Davis Road Ecology Center Interactive Map Tool

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.