Twelve years ago, scientists at UC Davis began a survey of the southern end of San Francisco Bay — the Lower South Bay — to see how fish responded to the South Bay Salt Ponds Restoration Project. They discovered an unexpectedly diverse and robust aquatic community and a previously unknown spawning ground for the longfin smelt (Spirinchus thaleichthys), listed as endangered in California and a candidate for federal protection because of its declining numbers.

The team, led first by Jim Hobbs and now by Levi Lewis, has complied an invaluable long-term dataset and enhanced our understanding of the surprising ecosystems of the bottom of the Bay. In addition to journal publications, their findings have been shared in blog posts by amateur naturalist Jim Ervin, who rides with the sampling crews and documents which fish the trawl brings up: “Every single month is a memorable experience,” he reflects (see Natives Who Can Rough It, this issue).

The team is based in the Otolith Geochemistry & Fish Ecology (“OG Fish,” informally) Laboratory in UC Davis’ Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology. Hobbs, who originally ran the project, studied with fish scientist Peter Moyle at Davis and returned there as a research scientist in 2009 after postdoctoral work at UC Berkeley. He met Lewis (“a close colleague for 20 years; super-smart”) at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory.

Lewis grew up near the ocean in San Diego and spent a lot of time fishing. “I wanted to go into fisheries science — something related to conservation,” he recalls. After undergraduate work at Davis, he got involved with coral reef ecology, a specialization with limited opportunity for fieldwork in California. Hobbs recruited him for the OG Fish Lab, where he became principal investigator for the South Bay surveys when Hobbs moved to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) in 2019. Hobbs continues to collaborate with the project.

The southern end of San Francisco Bay has taken a lot of abuse in the last couple of centuries. Long before the conversion of tidal wetlands into salt-production ponds, the Lower South Bay became a repository for raw sewage, a major culprit in the local demise of oyster farming at the end of the 19th century. Later, waste from the Santa Clara Valley’s fruit canneries overwhelmed tidal sloughs, causing massive fish kills.

As the city of San Jose grew, its sewage discharge became the largest stream flowing into the South Bay. By the 1970s, the neighboring city of Milpitas had become known as “the armpit of the Bay.” Conditions changed with the passage of the federal Clean Water Act in 1972 and the development of improved wastewater treatment technology. When the restoration of 15,000 acres of former salt-production ponds to a more natural state began in 2006, marking the largest wetland-restoration project ever undertaken on the West Coast, no one considered the South Bay a particularly healthy habitat for fish.

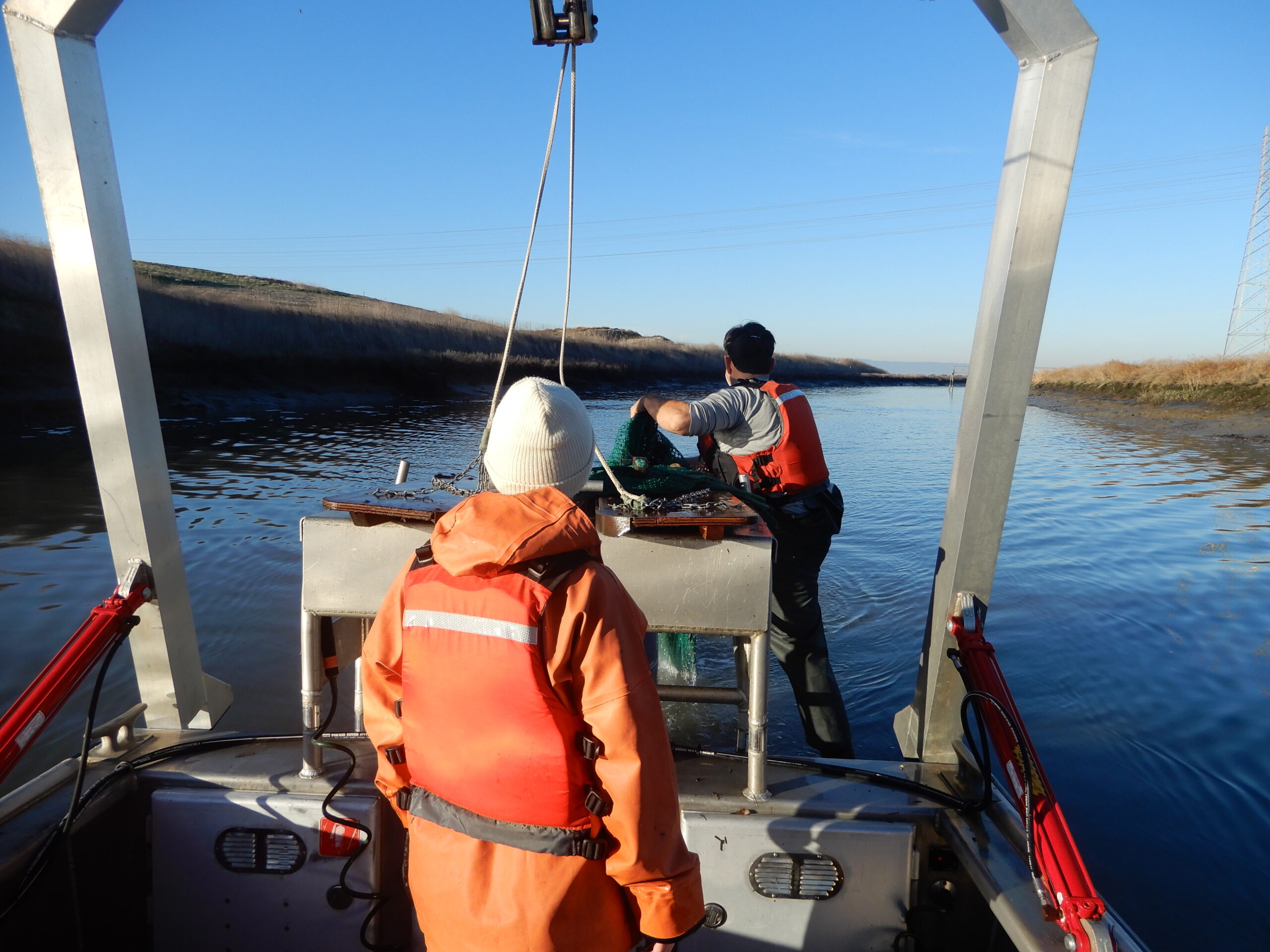

The fish survey began in 2010 in three of the restored salt ponds, later expanding to 20 stations for broader coverage of the Alviso Marsh Complex. Crews use an otter trawl, whose name may be an ironic tribute to the fish-eating mammal, to catch fish and the larger marine invertebrates. At each station, they measure key environmental parameters: dissolved oxygen and the temperature, salinity, and clarity of the water.

The otter trawl is well suited for catching juvenile and small adult fish; larger, more mobile fish like striped bass and leopard sharks often evade it. Even with that limitation, and without sampling habitats other than navigable tidal sloughs and ponds, the 2,400 trawls through 2021 yielded 66 species of fish and 30 of invertebrates. The same set of species used the restored ponds and the adjacent sloughs. Sixty-eight percent of the fish and 58 percent of the invertebrates were native species. When compared with four years of data from comparable trawls in San Pablo Bay, the Lower South Bay had ten times the abundance of fish and twice the species diversity.

What accounts for those differences? “The upper and lower estuaries are very different types of estuary,” Lewis observes. “The upper estuary is a classic estuary with a salt wedge and major freshwater flows. The Lower South Bay is a Mediterranean-type lagoon with seasonal flows from winter rains and relatively dry summers.” In that respect it’s more like estuaries to the south, from Morro Bay to San Diego. Hobbs says that high-salinity conditions in the South Bay bring in more marine species, increasing the species count. Both also point to the influx of nutrients from the South Bay’s wastewater treatment plants as a stimulus to food production, which is lacking in the Delta and northern Estuary.

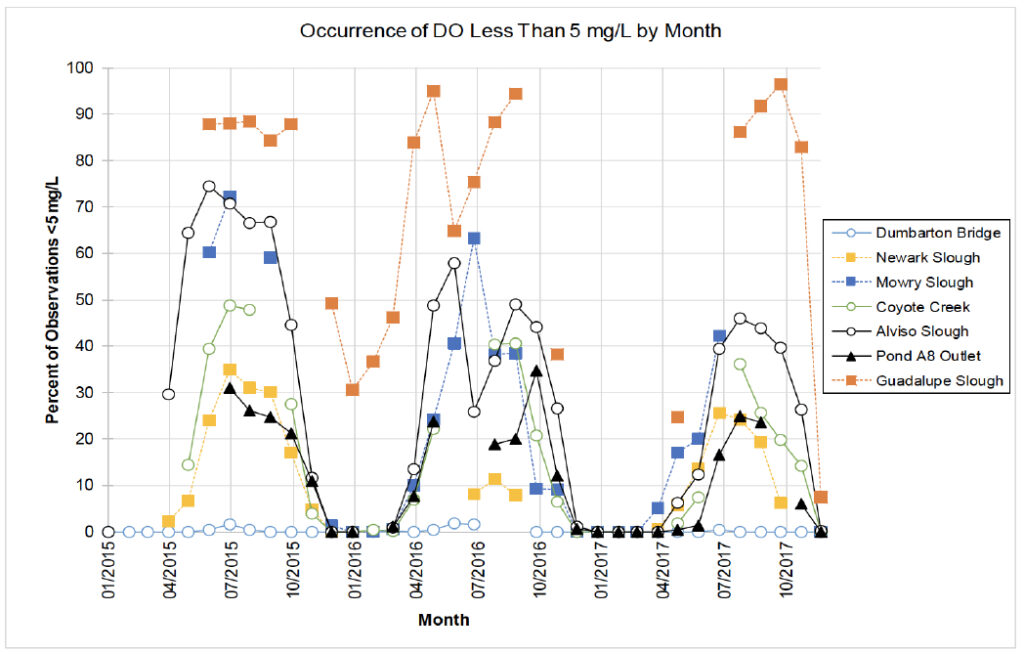

As the researchers looked for patterns in how fish responded to dissolved oxygen (DO) and other environmental parameters, it became clear that there was no such thing as a typical fish. Almost all fish get the oxygen they need from the water they swim in; conditions of hypoxia, with extremely low oxygen, can be lethal. Above those extremes, responses can be all over the place.

In the South Bay, different species responded positively, negatively, or not at all to DO levels. For most species, abundance showed stronger associations with seasonal changes in temperature and salinity, weaker with DO and turbidity. Longfin smelt and American shad numbers correlated with high DO and cooler temperatures. Overall, catches were higher during the summer in warmer, fresher waters with low DO, a trend driven by native northern anchovy and non-native yellowfin goby; species richness was lower in those conditions. California halibut catches correlated with higher DO.

“Our most significant finding is the fact that longfin smelt were reproducing down there,” says Hobbs. The species was caught in surveys by the South Bay Discharge Authority in the 1980s, but spawning wasn’t detected. (Jim Ervin unearthed the data from those surveys in an office basement.) The Davis team found large aggregations of smelt in reproductive condition from 2011 on. In 2017, one of the wettest years on record, larval longfins confirmed local spawning and were observed again after another wet year in 2019.

It’s unclear how the larvae fare after hatching. According to recent studies, South Bay larvae are feeding better than their North Bay counterparts, but that doesn’t translate into a higher growth rate. In the language of population biology, is the Lower South Bay a source or a sink for longfin smelt? “It’s too early to tell,” says Hobbs. “I’m probably more concerned it could be a sink.” The South Bay can warm up fast, and longfins are sensitive to warmer temperatures.

Unlike the Delta smelt, the longfin isn’t endemic to the San Francisco Estuary. Its range extends north to the Gulf of Alaska, with landlocked freshwater populations in Washington State. “We know very little about those other populations,” Hobbs notes. “We’ve been trying to connect with other researchers.” Longfins move among freshwater, brackish, and saltwater habitats, some dispersing into the ocean. There are indications of gene flow between Estuary longfins and their northern kin. Hobbs says the status of the northern populations could be a big issue if the US Fish and Wildlife Service lists the longfin under the Endangered Species Act; a status assessment by USFWS is currently out for public comment.

Most of the team’s catches are returned to the water, but not some of the longfins. For the last three winters, adults have been collected as brood stock for UC Davis’ Fish Culture Conservation and Culture Laboratory in Tracy, where captive rearing is being attempted as a hedge against extirpation. Others are harvested for analysis of their otoliths (the ear bones whose chemical signatures help trace a fish’s movements), livers, and stomach contents.

Longfin smelt were what hooked Jim Ervin when he first learned about the South Bay Fish Survey in 2012. Levi Lewis now calls him the Lorax of the Estuary. READ MORE

Although native fish species predominate, the Lower South Bay has its share of non-natives, including striped bass and several Asian goby species. The inland silversides, a relative of the native grunion and topsmelt, may be the most problematic. Silversides from Oklahoma were introduced to Clear Lake in 1967 to control gnats. They weren’t particularly good at that, but their burgeoning population altered the lake’s food webs and may have helped drive the endemic Clear Lake splittail to extinction. Silversides had reached the Estuary in 1975. Although they weren’t caught in the Lower South Bay until the 1980s, they’re present there now in alarming numbers; thousands are being caught in the managed ponds alone.

These innocuous-looking fish are as fecund and voracious as Star Trek’s tribbles. Fish biologist Carl Hubbs calculated that a female could produce 15,000 eggs in a single summer, at a rate of 200 to 2,000 per day. They’re short-lived, but capable of reproducing in their hatching year. “They’ll eat everyone out of house and home,” says Hobbs. “They’ve caused havoc in the Delta, short-circuiting production for native fish by eating zooplankton that’s food for baby fish.” Their diet includes eggs and larvae of other fish, particularly those that spawn in nearshore shallows like the longfin smelt and the endangered Delta smelt.

The fish community isn’t the only thing that’s changed in the South Bay. Dams have stoppered the creeks and rivers that freshened the Bay, and the ground has subsided up to 12 feet in some areas due to groundwater depletion. The wastewater treatment plants are now the South Bay’s only major source of fresh water, contributing 100 million gallons per day. “Treating and returning wastewater is a pretty good use of that effluent — a beneficial use,” Lewis reflects. “It produces an estuarine gradient that otherwise wouldn’t exist.”

Treated effluent is high in nitrogen that stimulates phytoplankton growth, but it can also cause hypoxia — dangerously low oxygen levels. “Nutrients can be a blessing and a curse,” says Hobbs. “The system is right on the knife edge of being overproductive. It’s not in a really bad spot yet. We haven’t seen hypoxia persisting for many days, unlike in Chesapeake Bay where good chunks of the system are hypoxic for the whole summer.”

Low-oxygen waters may provide a temporary refuge from predators for sticklebacks and sculpins. The researchers recommend studies of how native fish respond to DO levels. “A lot of the standard hypoxia criteria are based on fish species that aren’t in our estuary,” Lewis points out.

One red flag is that occasional fish kills — of species including striped bass, sturgeon, and leopard sharks — have been observed in the managed ponds like A16 and A18 in late summer and fall when wind conditions change and water and fish are trapped. Because of that, Hobbs says he has challenged salt pond restoration objectives that called for equal numbers of tidal and managed ponds: “When you put in water-control structures you’re responsible for water quality and all the biota. It takes persistent management.” Managed ponds may be good for waterbirds, less so for fish — another dilemma of managing for a whole ecosystem.

Since San Jose attained its present city limits in 1969, its population has roughly doubled: from 495,000 then to more than 1 million today. Santa Clara County followed the same trajectory. “The Lower South Bay’s ecosystem is really good, considering [that increase in population],” reflects Lewis. “One big intervention that significantly reduced our per-capita impact on the ecosystem was going to a really high standard of wastewater treatment.”

San Jose has, in fact, become a model for other cities like Sacramento, now overhauling its own treatment system. “There are still impacts, but if the ecosystem has improved that much since the 1950s, we’re doing something right,” he continues. “Fish biomass and diversity in the Lower South Bay are high. There are abundant forage fish populations and striped bass and sturgeon fisheries. And we’re restoring more and more tidal wetlands every year. The story of San Francisco Bay is a story of hope.”

Monitoring fish, other wildlife, and environmental conditions is essential to continuing to do things right. It’s been a challenge to keep the Lower South Bay project going. “It’s on a shoestring budget,” says Lewis. “The researchers really sacrifice themselves.” Hobbs put up his own money to plug a year-long gap between contracts with the South Bay Salt Ponds Restoration Project. The last two years of monitoring were supported by the San Jose-Santa Clara Wastewater Facility, with supplemental funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and CDFW. The San Francisco Estuary Institute has contributed funds for special studies, analysis, and fieldwork.

Hobbs says federal money may be forthcoming if the longfin smelt is listed. But the future of the long-term monitoring program itself remains uncertain. Such programs are vital to successful management of the Estuary, he notes: “We don’t get a broader picture of what’s happening with the ecosystem without those.”

Top photo: Lowering the trawl net in a South Bay slough. Photo: James Ervin

LINKS